Colin Powell, soldier, statesman, and lifelong public servant to the imperatives of empire, died yesterday, at the age of 84. He is survived by his wife, three children, and four grandchildren. He was predeceased by his eponymous doctrine and at least 185,000 Iraqi civilians.

Born in 1937, Powell preceded by a decade the institution that would define both his life and much of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The 1947 National Security Act birthed the Department of Defense, coalescing the bureaucratic innovations in managing war and espionage cobbled together during World War II and setting the US on a permanent war footing it has never left since. Harry Truman’s ordered integration of the armed forces in 1948 made possible Powell’s specific path into and through the military, but it was the 1947 act that ensured the US would always perceive itself in existential peril — and adopt a military-first foreign policy to match.

Powell joined the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps as a student at the City College of New York and was subsequently commissioned into the US Army in 1958. This was the relative lull between active US involvement in Korea and Vietnam, but it was still an era of the peacetime draft. The draft, kept in place by the same general who ran it during World War II and would continue to run it until 1970, was maintained in part to drive volunteer enlistment.

In 1962, Powell spent a year advising the South Vietnamese army. He would return to Vietnam as a major in July 1968, working on a general’s staff. In that role, in November 1968, he opened a letter written by Tom Glen, an army specialist whose tour had ended. Glen’s letter, addressed to General Creighton Abrams (at the time in charge of the war effort in Vietnam), detailed American war crimes, though it did not name specific participants. Powell, following the lead of Glen’s former commander, said at the time it was unfortunate Glen had not brought up his allegations immediately, so that they could be resolved through proper channels.

Glen’s letter arrived eight months after US soldiers massacred five hundred civilians at My Lai, though it would take a second letter by a different veteran to alert authorities to that cover-up.

In his 1995 autobiography, Powell reports his version of what transpired when an investigator with the army’s inspectorate general sat with him for an interview. Powell describes flipping through the monthly reports of the unit that committed the My Lai massacre and noting that “128 dead” killed by one unit was an unusually high number but possible in the regular course of war. The inspector general’s recording of the interview, as David Corn reported in 2001, contained no such clear realization.

Prior to the letter that revealed My Lai, “the Army promoted the story that C Company had killed 128 VC and captured three weapons in the March 16 action,” Corn writes. Powell, in his memoirs, was “repeating the cover story, not recalling what was actually in the journal.”

Faced with two whistleblower attempts to reveal an event now synonymous with war crimes, Powell deferred to his command and instead held the company line. In 1971, he testified on behalf of a general who ordered the shooting of unarmed civilians from helicopters during the general’s trial for war crimes, arguing that such action made sense given the difficulty of counterinsurgency warfare among a hostile populace.

“Powell’s small but unhesitating contribution to the My Lai cover-up is hardly surprising,” writes historian Jeffrey J. Matthews:

His superiors had clearly set the example. Little in Powell’s personal development or professional training prepared him — much less encouraged him — to critically assess and consciously challenge his leaders. Moreover, to have done so would have derailed his promising career.

That “promising career” would bring Powell, after a time commanding US forces in Korea, into the confidence of Caspar “Cap” Weinberger, Ronald Reagan’s secretary of defense. Powell served him as a senior military assistant. It’s a uniformed role designed to offer the civilian administration the depth of military knowledge, but it’s also a job that implicates those who perform it in the politics — and misdeeds — of their civilian charges.

Weinberger was among several Reagan officials involved in selling weapons to Iran so that the Reagan administration could funnel money to the Contra counterrevolutionaries in Nicaragua. Weinberger was eventually indicted for five charges related to Iran-Contra but preemptively pardoned by president George H.W. Bush before he went to trial. Powell was present at at least one meeting in 1985 to negotiate the covert sale of arms in exchange for hostages — and reportedly knew much more about the entire operation.

The first inklings of what would become the Powell Doctrine emerged in this era. In a November 1984 speech before the National Press Club in Washington, DC, Weinberger outlined a series of conditions under which it was appropriate for the United States to go to war. Like the “All Volunteer Force,” which replaced a partially drafted military with a fully professional one, the Weinberger, and later, Powell Doctrines were tools designed to facilitate the use of military force and smooth the way for ongoing, open-ended involvement in conflicts abroad.

The doctrines are commonly misread as caution against going to war, but this understanding misses the historical context of their origin. Both doctrines were framed as a response to, broadly, the US failure in Vietnam, and more directly to the death of US marines in Lebanon in 1983. The lesson Powell drew wasn’t just that counterinsurgency is a hard kind of war to fight. His other lesson was that the American public needed to be sold on a war for the military to be allowed to wage it, and it was easiest to make that sale if a war was promised to be fast, supported abroad, and with an exit strategy in hand.

That the doctrine was more permission than constraint is apparent in how Powell, by then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, described the success of the US military in 1992. “Over the past three years the U.S. armed forces have been used repeatedly to defend our interests and to achieve our political objectives,” Powell wrote:

In Panama a dictator was removed from power. In the Philippines the use of limited force helped save a democracy. In Somalia a daring night raid rescued our embassy. In Liberia we rescued stranded international citizens and protected our embassy. In the Persian Gulf a nation was liberated. Moreover we have used our forces for humanitarian relief operations in Iraq, Somalia, Bangladesh, Russia and Bosnia.

For a generation, it is this version of Powell in 1992 that is fixed forever in memory, promising the benefits of a magnanimous and strong hegemon to the whole of the world — provided, as he argued in the next paragraph, they can keep the Pentagon funded.

The no-fly zones over Iraq, maintained by the United States and regularly patrolled by the air force from the summer of 1992 to the invasion in 2003, suggest that the exit strategy comprising one of the three pillars of the Powell Doctrine was in fact a phantom third limb, easily ignored and banished from relevance.

Powell stuck around the Clinton administration long enough to implement the formal “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” ban on military service by out queer people, then left public office until president George W. Bush named him secretary of state, borrowing Powell’s gravitas to legitimize the administration’s court-decided installation.

Because of that role, Powell will forever be synonymous with his testimony before the United Nations in February 2003, where he cited flawed intelligence and flimsy evidence to make the case for a second US invasion of Iraq. That war, which has likely killed three hundred thousand people, was a foregone conclusion by the time he went before the United Nations — the real fight over whether the Bush administration would invade Iraq, after it was already in Afghanistan and refusing to exit-strategy a way out, took place in the summer and fall of 2002. But Powell played a critical role in selling the war to the American public.

“For those in Washington less committed to invading — but open to it — Powell was less a man than a north star,” writes Spencer Ackerman:

As long as he remained in the Bush administration, it meant that there were voices of sanity around Bush, and so it became possible to see Bush as something other than delusionally bellicose — or, at least, as a delusionally bellicose man restrained by the sobriety and responsibility of the hero at Foggy Bottom. This was a point that Cheney, Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, and Bush were happy to see take hold, since it so perfectly served their invasion — so long as Powell kept playing his role.

“The president wanted his approval ratings,” wrote George Packer in 2013, in a reflection on what giving the speech before the UN meant for the reputation Powell had built:

The White House wrote a speech for him to give, forty-eight single spaced pages. He had a week to get rid of all the lies, and that wasn’t enough time, and there never could have been enough time, for he didn’t stop to challenge its premise.

Powell gave the speech, served out his term as secretary of state, and then departed the Bush administration and public service altogether in January 2005, as soon as Condoleeza Rice was confirmed his successor. In the 1970s, his loyalty to the institutions he served had marked him for a promising career. By refusing to stake his reputation on opposing a war he knew to be based on false pretenses and in response to no imminent threat, Powell authored the deaths of hundreds of thousands and material harm to millions more.

Powell’s course through the institutions of American military power has been subject to much hagiography. The man’s reputation was durable despite his role in authoring-by-acquiescence the Iraq War. His signature achievement was not so much a doctrine that mitigated war as a way for polite society to argue that the US wars launched in their middle years were just and sustainable, unlike the military misadventures undertaken in their youth.

To tell the story of the lives of figures like Powell is to repeatedly encounter all the moments in which they prioritized service to power over obligation to the people they serve. Powell’s autobiography included the cover-up number for My Lai — but framed it as him leading the investigation to useful evidence, illustrating at least a desire to be on the right side of history. His 1990s insistence on multilateralism in international problem-solving reads as fully cynical because of how thoroughly Powell sacrificed that goal on behalf of continuing to serve a president who disregarded his counsel.

To the extent that he justified his continued presence as a moderating influence, that he stuck around after abandoning the leverage resignation would have offered meant Bush was free to keep him as a totem against criticism. By remaining in his role, Powell set a template for how future officials, uniformed and civilian alike, would find their image used to commit malfeasance in office, on behalf of cynical presidents who would discard them the moment they came into real conflict.

Those choices had tangible consequences in the corpses stacked high throughout the world. For people who lived through the lead-up to and launch of the Iraq War, it stands as a uniquely grotesque tragedy that was fully avoidable, fully predictable, and yet entirely imminent once the war drums began beating. For young people growing up in its wake, it is but one of many such results, the inevitable outcome of a domineering national security state that bends all who wish to serve it — and even those who might wish to redirect its energies — to the same purpose.

It is impossible to say what would have come from Powell insisting on multilateralism, to quitting the Bush administration over its desire for an Iraq War of its own at any cost. It is possible, in the universe where Powell had the courage of his convictions while in office, that the existential crisis of the twenty-first century, which cannot be solved with brute military force, could be undertaken without decades of bad faith and spilled blood.

But we do not live in that universe. We live in this one, where excellence, tireless devotion, and unwavering loyalty mean very little when they are in service to the unceasing machinery of war.

This article first appeared on Jacobin. Read it here.

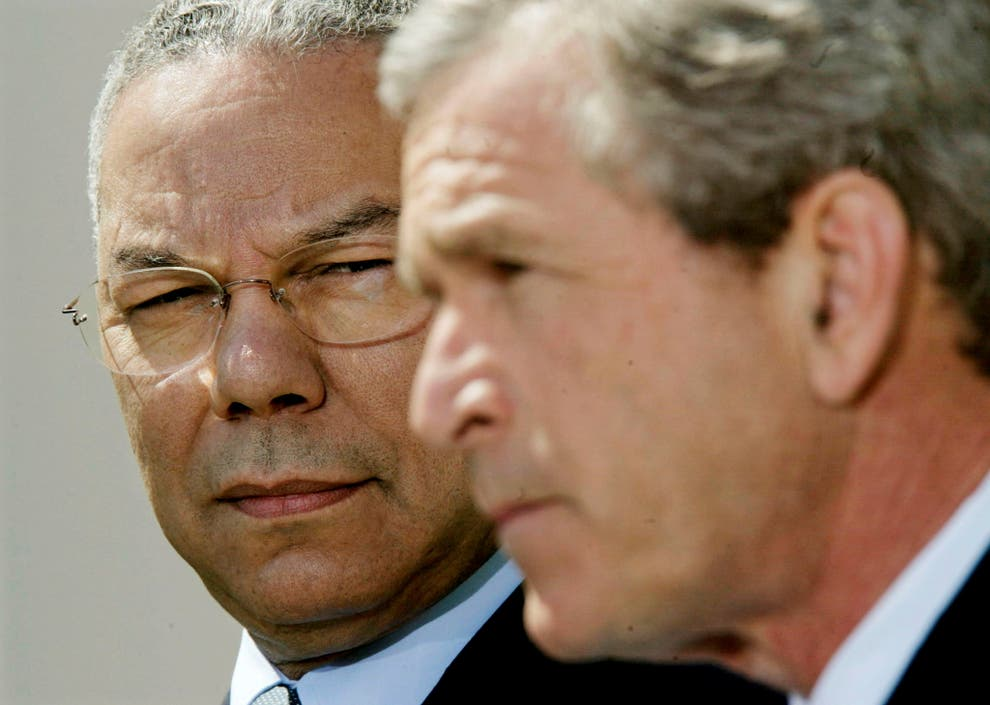

Featured image credit: Reuters