A few weeks ago, a play on M.K. Gandhi’s assassin, Nathuram Godse, was staged at the National Theatre’s largest stage in London.

“What are you staring at? Have you never seen a murderer up close before?” says Shubham Saraf, oozing with confidence, as he appears on the Olivier stage. “Take a good look. You have paid good money to be here.”

Under this mischievous and playful beginning lies the seriousness of the subject. The murderer in question is the Hindu nationalist, Nathuram Godse (played by Saraf). “This is my story and I will tell it my way,” he says.

With her able excellence, playwright Anupama Chandrasekhar has attempted to touch upon a tragic episode in modern India — a story of division and hatred that has its roots in colonialism. This comes at a time when Hindutva forces are continuing to fracture Indian society. The lavish political thriller that has won some critical acclaim is a riveting psychodrama that asks why Gandhi was killed. The intention of the play is to also act as a mirror to a generation of UK-based audiences who have never been taught about colonialism and the atrocities conducted by the British Empire.

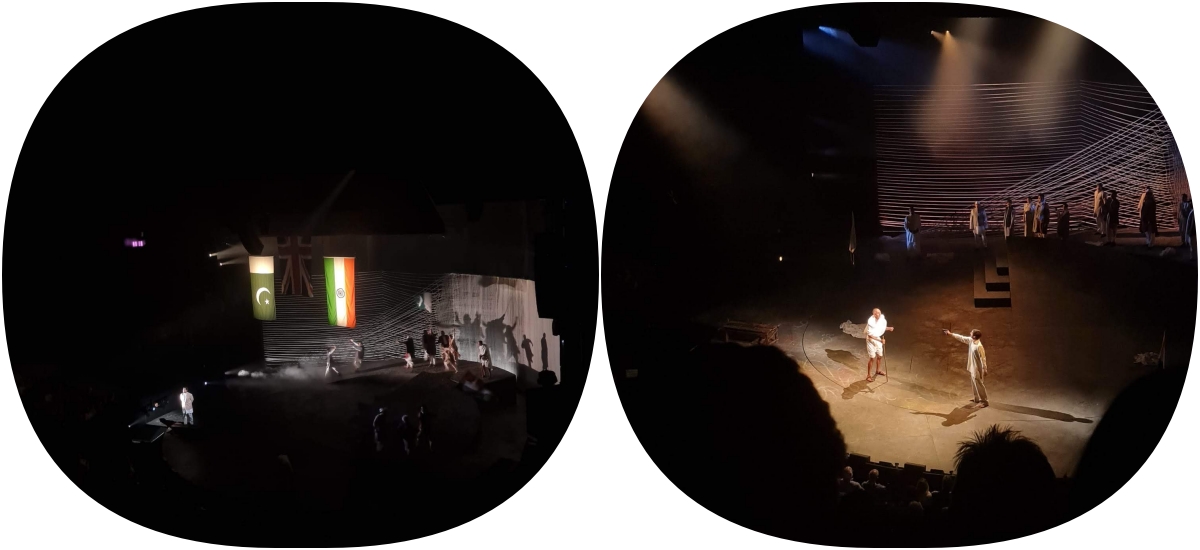

The Dandi March is brought alive on stage. So is the Partition, but with no bloodied action. Director Indhu Rubasingham, along with the brilliant set designer Rajha Shakiry, does well to infuse the world of 20th century India with life, bringing to focus that zooms in and out of the village streets and historic marches against the Empire, picked out dextrously by Oliver Fenwick’s lighting. They ensure that many scenes, spaces and arguments stream into one another by repeatedly using the theatre’s enormous revolve. This kind of impetus is advantageous in historical plays such as this since it necessitates extensive explanation.

A still from ‘The Father and the Assassin’. Photo: Marc Brenner/National Theatre

Thrillingly exploring Nathuram’s past, the play uncovers his truly unusual upbringing: raised as a girl by his parents (his superstitious parents lost three sons in infancy) and his conviction that he is destined to be a “somebody”. India’s struggle for freedom is paralleled with Godse’s struggle for recognition and a fractured identity, where Gandhi serves as both the idealised father of India and Godse’s father. After being initially motivated by Gandhi, he later meets the radical Hindu nationalist Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, who dissuades him from engaging in non-violent protest.

Godse’s games with his childhood friend Vimala turn into a dichotomy of ideological style and substance, as she signifies Gandhian peaceful protest with an open heart, whereas he relentlessly is seen controlling the narrative and pushing her (and the Gandhian ideas) out of his tale. He hopes his disagreements with Gandhian principles will fade away “like an irrelevant apostrophe”.

Godse worshipers — and his cult — is no more marginal. It is a mainstream reality of ‘New India’. Its members include not only BJP MPs, but also significant Sangh ideologues. They continue to spew hatred against minorities in India, all in the name of making democratic-republic India a Hindu rashtra.

However unravelling and intertwined, the play profoundly worries on historical and factual levels. First, the omission of not mentioning the name of a radical organisation that Godse was deeply associated with, is an enabling agent in contemporary times keen on discarding and not recognising the past. Throughout the play, there is not even a single mention of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) or Hindu Mahasabha. The concern only compounds when it is made for the Indian diaspora, who consume news from mainstream media, which is often a site of propaganda, and who have contributed financially to such institutions and hailed the idea of ‘New India.’

The second startling portrayal is the presentation of Godse as an opponent of Gandhian philosophy. Though he was the one to hold the pistol, it is enormously misleading, unfair and inappropriate to Savarkar, as Savarkar was instrumental in waging an intellectual conflict with Gandhi. It further promotes the battles of ‘binaries’ in the public discourse, which sadly is the new norm, and hollows out the foundational root cause of the conflict by putting both the figures on an equal pedestal.

In an era where narrative change, rewriting and reconstructing histories, propaganda, disinformation and fake news is all-pervasive, it becomes difficult to empathise with the intent behind the production. As the space for the ‘argumentative Indian’ shrinks and ‘Indians themselves become minorities,’ we need to remind ourselves of and re-examine the idea to tell facts and emulate truth from them. Likewise, as hate continues to foster, it is a grim reminder that India cannot afford further air-brushing and subversion of truth.

As ‘Jai Shree Ram’ continues to be used as a weapon against India’s minorities, the play does not include Gandhi’s famous last words: “Hey Ram.”

Kalrav Joshi is an MSc candidate of Media, Communication and Development at The London School of Economics and Political Science. He is fervently interested in politics, development, democracy, culture and technology.

Featured image: Kalrav Joshi