Whenever I would talk about the Partition with my grandfather, words like pain, separation, loss, deprivation, death, home, violence, senselessness, division, and madness would often make their appearance during the conversations.

“What did it feel like when you migrated to India after Punjab was broken up?” I asked.

“I had little idea about what the Partition really meant for us,” he said.

My grandfather came from a generation that was able to enjoy the fruits enabled by those who fought for freedom from the British Raj. They were grateful for their rights as citizens and mindful of their duties. My father recalls how my grandfather, on the first day of every year, would excitedly announce, “Panditji has predicted that this year India would become a superpower.”

For 40 years after Independence, my grandfather worked for the Punjab government. He was a devout Hindu and said his prayers every day. During the last two years before his death, he suffered from dementia. He couldn’t differentiate between dawn and dusk. There were times when he would wake up at five am, say his prayers, and then ask for dinner from my grandmother. My grandmother, understandably irritable, would yell and request him to go back to sleep.

My grandfather had been bedridden for the last 15 years of his life. We had placed his bed in the room adjacent to the balcony so that he could get some fresh air. He never demanded to be entertained. Although, a good game of Rummy, Teen Patti, and Ludo with my father every Sunday used to cheer him up and bring out his competitive side.

Discussions reminiscing about “the good old days in pre-Partition Punjab” frequently came up. One time, my father asked, “What do you remember from the Partition? Did the family suffer any loss?”

My grandfather took a few seconds to gather his thoughts and said, “Loss? Hmm. Everyone lost something.”

Also read: My Grandfather’s Bedtime Tale of Tolerance

My father then egged my grandfather on to see how he would respond, “Doesn’t your blood boil when you think of the Muslims? Don’t you wish to avenge the loss to the Hindu community?”

My grandfather pensively added, “We saw the worst of humankind during that time and the only thing I learned was that violence does not do any good. Violence can never be the answer to anything. Whom am I to avenge? It wasn’t a loss to my or someone else’s family. It was a loss for humanity.”

My grandfather hailed from Jhang, a district in Punjab province in Pakistan that was notorious for its hot-blooded people who would not think twice before picking a fight. His general views on violence and revenge, hence, would come as a surprise to anyone that hailed or knew about the stereotypes associated with the region.

Since his birth, my grandfather lived with his uncle and aunt. The couple were without a child and loved him as his own. My grandfather’s parents and siblings had crossed the border before and trusted the couple to safely get the teenager across the border with them. When I asked him about the journey, he said, “My uncle was killed by a frenzied mob. I was stabbed in the chest with a knife and thankfully recovered. My aunt was forced to convert and marry a Muslim man. But both of us were able to flee and somehow managed to cross the border.”

My father questioned the veracity of the claim about his aunt being forced to convert. He explains to me in a hushed tone, “If that were the case then why would a man, who got a woman to convert and marry him, let her flee so easily? Maybe dementia has clouded his memories.”

My grandmother was quite the opposite. She was upset about the Partition and how it forced them to leave their homes with the British rulers sending them off to settle in a foreign land. This foreign land soon became their new adopted home. She along with her family moved to Sunam village in Sangrur district in Punjab.

But she seldom showed her bitterness about it. She mostly stuck to the response, “It was what it was. There’s no point in discussing it now.” My grandfather used to nonchalantly chip in saying, “You’ll always be a jhangan.” It was heartening to see how both of them with such differing views could still manage to respect each other’s viewpoints and not be dismissive.

I often wonder how my grandfather would react to the polarisation in recent times. With people still losing lives because of communal madness, would my old man still be asking, “Whom are we to avenge?”.

Aastha Maggu is a resident of Delhi and works as a Development sector professional. She tweets @sthamaggu.

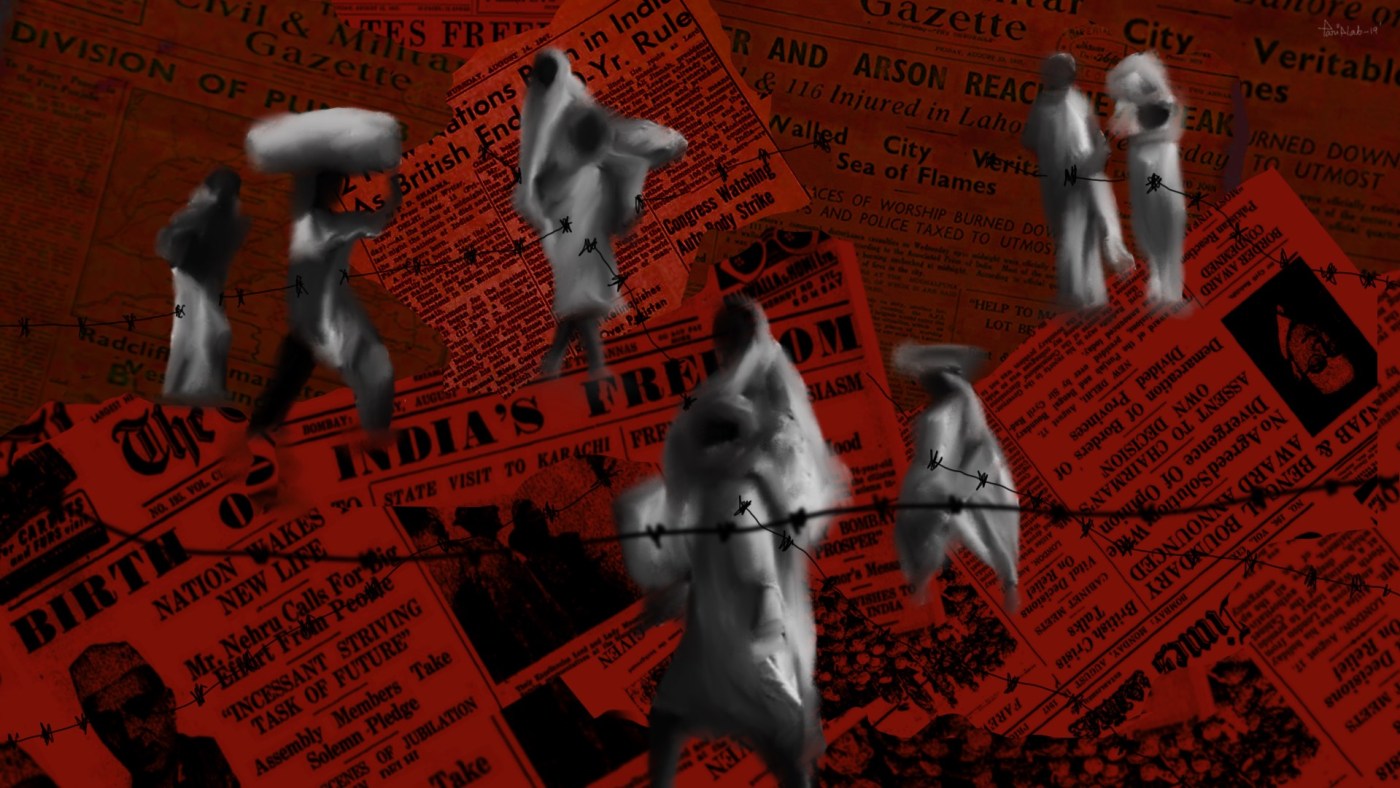

Featured image credit: Pariplab Chakraborty