“What are the concerns that you carry in the new year from the old one and what are the challenges that you’ll face? Most importantly, is there any hope, anything that we can expect from this new year?” a friend asked.

Usually people talk about new year resolutions. What could they be for us as a people, as Indians? For them to be sincere, it will be necessary to take stock of our condition with honesty.

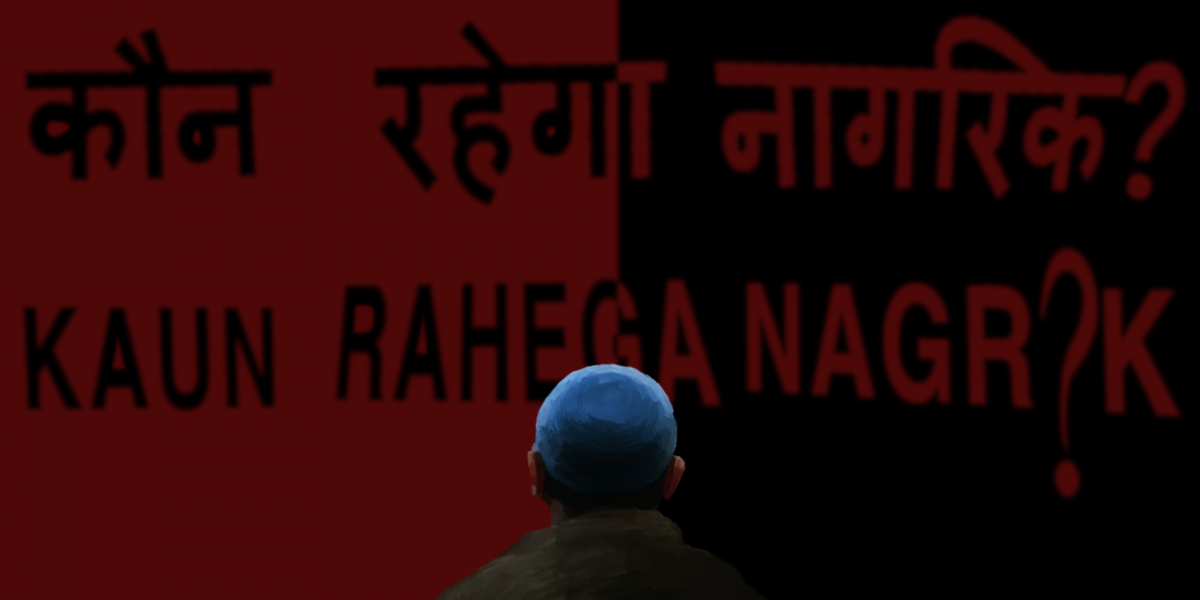

What is the biggest worry we have today? Some people point at the growing schism between communities in the society, mainly between Hindus and Muslims. It is only superficially true but not the right description of reality.

The real problem is the production of a Hindu mind in India which is supremacist and suffers from a sense of exceptionalism. A supremacist mind is also an insecure mind: narrow and closed for external influences. This closed mind has become soft because of this inwardness. It sounds bad but it is true that today’s average Hindu mind is full of hatred: hatred towards foreigners and outsiders.

There can be different types of outsiders. They are definitely Muslims but also Christians. The relationship of this mind with these ‘externals’ can only be of enmity. Hinduism or Sanatan Dharma (what this term really means, the self-declared Sanatanis cannot tell you even when they are proud of it) is the best, most generous and non-violent in the world! How can then the Sanatanis Hindus accept that they have become isolationist and hateful people? When told about this they get furious.

Another concern is that in the name of finishing the incomplete task of history – that is taking revenge for the defeat of their ancestors at the hands of the Mughals or for the Partition – these ‘Sanatanis’ justify their hate and violence. These hate-filled Hindus take pride in calling themselves ‘awakened Hindus’. Hindus have woken up now and you cannot take them for granted, they say.

Also read: Lies, Insistence and Disregard for Evidence: The Journey of ‘Love Jihad’ Laws

This Hindu supremacism considers other religious communities as inferior and as outsiders in India. Along with this, the return of caste supremacism is another concern.

We are witnessing a counter-violence against social justice by the so-called ‘upper castes’. It is leading to another kind of violence. The Hindu society, which looks united only against Muslims and Christians, is badly fragmented and riddled with mutual caste hatred and competition, which does not take long to turn into violence.

The birth and mushrooming of various cadre organisations, new ferocity in caste-based celebrations is the feature of our times. Caste had never gone but there was some hesitation in making it your identity marker. Now it is done with pride. And we are talking about our youth.

Thus, our country and the society are victims of unprecedented fragmentation. It has made it difficult to imagine a common social or national interest. Any concept like ‘The People of India’ seems impossible. For this reason, when the farmers took to the streets with their interests, the government and the media tried to prove that they are not farmers but Khalistanis.

To an extent, it was successful in sowing the seeds of suspicion against these farmers among the Hindus of north India.

Hindu and caste supremacy and the role of media

Another big concern is that the Hindu society, with the intoxication of supremacism and filled with the false sense of responsibility to correct the past, is now losing its comprehension. In a way, this Hindu society is a victim of cognitive dissonance.

Another concern which is bound to deepen in this new year is the gradual elimination of the idea of knowledge in society. Knowledge has been replaced with singing the paean of the great knowledge that our ancestors had produced. What we now learn is that “the history of India is the oldest in the world, it has a 12,000 years long history, India is the mother of democracy, Sanskrit is the mother of the world’s languages, etc.”

Also read: What’s a ‘Corrected’ Version of Indian History?

It was necessary to destroy the sense of modern knowledge to paint the intellectual community as enemies of the people. Intellectuals try to wake this society up to reality. That is a crime now.

By resorting to this supremacism, the Bharatiya Janata Party has made Hindutva the driving force of public opinion and appointed itself as its spokesperson and protector. Other political parties are unable to challenge this majoritarian mindset. Because of this, Indian democracy itself has been hijacked.

This majoritarianism is the disease of north India. Due to its sheer population size, it has the maximum number of parliamentary seats, which helps it control the rest of India.

The media is no longer the carrier of information. Information has been replaced with anti-Muslim hatred. The media is proactively fabricating an anti-Muslim Hindu. This Hindu is essentially opposed to Dalits and the poor and against any mass movement.

Muslims are friendless in India – barring the intellectuals. Not only the BJP, the entire state apparatus is against Muslims. They are being denied rights in Kashmir, being pushed into the corner in Assam and are being persecuted by the nexus of law enforcement agencies and goons across the country.

Can it go on forever? Premchand had warned a century ago that any community with self-respect cannot tolerate this insult and torture for long. Muslims are still hopeful about the democratic possibility of India, but the way constitutional institutions are turning majoritarian, this belief will not last long.

Another concern is the end of the idea of justice. Bulldozers have become a symbol of justice. The apathy of the judiciary in making corrections to this trend has worsened the situation. Apart from this, the majoritarian inclination is becoming evident in the judiciary itself. The judgments about hijab, economic reservation, Gyanvapi or Mathura controversies et al. are very telling.

Also read: The State of Justice in 2022

These are the concerns with which we enter the new year. Unemployment and economic inequality are also a cause of concern, but do they concern the Hindu society? So long as it remains in the grip of the Hindutva nationalist propaganda, it seems no temporal reality would be able to shake it.

The challenge is to liberate the Hindus from this toxicity. For this to happen, the walls that the media have created between the average citizen and reality must be demolished. There is a challenge to create a new network of information and knowledge. The challenge of keeping the idea of knowledge alive is huge. When all the centres and means of knowledge have been captured, how will it be done?

Will political parties be able to fight the majoritarian temptation? Will they accept the political agency of Muslims and Christians? Are they aware that it is no longer the time of the old competitive parliamentary politics? Their task is now not just to get power for themselves, but to rescue institutional democracy. Recognising the ‘extraordinariness’ of this political moment and determining their duty accordingly is a challenge for them.

Is there any hope then? There is no alternative to hope. But what does hope look like? Only struggles can be the real source of hope.

Muslims are fighting for justice despite lacking resources and remaining friendless. One has to realise the risk that they are taking when all the institutions are either indifferent or antagonistic to them. In a way, they are also giving courage to the courts.

The ‘Bharat Jodo Yatra’ has raised political hope. The Congress party’s return to its people is good news for India’s democracy. The meaning of politics is dialogue with the public. It is good that many non-Congress parties have also realised it.

Despite all odds, a good number of independent journalists and media platforms are now engaged in constructing a bridge of information. Students are coming back to the campuses after a long gap. We can hope that this youthful energy will renew our collective life.

We don’t have the luxury of hopelessness. It was on the last day of the passing year that we learnt that the families of the five Muslims in Firozabad, who were killed during the anti-Citizenship (Amendment) Act protests, have succeeded in persuading the court to reopen the investigation and reject the closure report of the Uttar Pradesh police.

One wonders what resources they had for this fight for justice to sustain! Did they have hope? The answer is that struggle is the only hope now.

Apoorvanand teaches Hindi at Delhi University.

Featured image: Pariplab Chakraborty

This article was first published on The Wire.