A 2008 report from Tehelka – mentioned in the book – tells us that nearly 80 years after the Mahad Satyagraha, a pond in Chakwara village was turned into a sewer by caste Hindus after the Dalits had won the right to use it — revealing the bitter irony of winning a Dalit resistance.

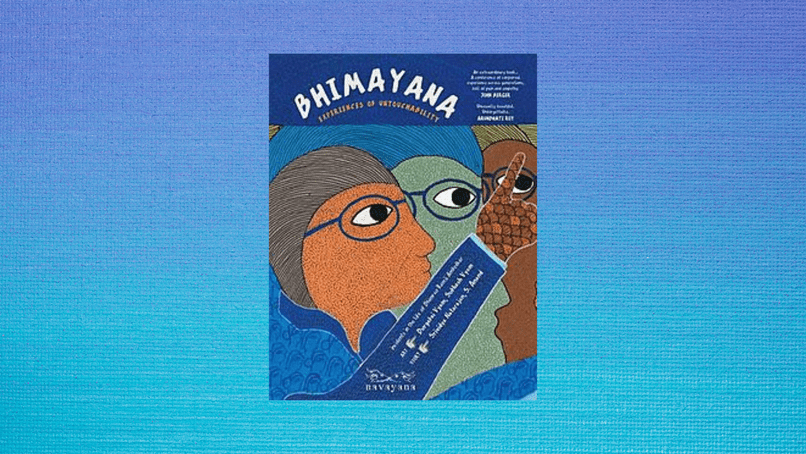

Bhimayana, the graphic novel written by Srividya Natarajan and S. Anand, is an account based on the experiences of untouchability and oppression faced by B.R. Ambedkar.

The title can be best described as a conversation between an apparently Dalit woman and a caste Hindu man waiting together at a bus stop. They speak about reservation in education and jobs and the woman starts taking the man through different incidents of social oppression to explain the dynamics of casteism in India. Irony, a constant element of the narrative, mirrors the anti-caste movements and current political climate of India.

The chapters in the book have been named after essentials like ‘Water, ‘Shelter’, and ‘Travel’, which are necessary for one’s survival. The chapter ‘Water’ highlights the struggle of a 10-year-old Ambedkar who is denied equal access to drinking water at school, and so, it gradually converted into a mass struggle for social equality in India. In ‘Shelter’, the story narrates the relationship between a Dalit person’s hope for shelter and life, and the hard choices to be made between the two.

Despite having a degree and a job, Ambedkar’s marginalised identity could never be accepted and become a reason for his potential death instead. The book is filled with Gond artwork by Durgabai Vyam and Subash Vyam. Originating in a marginalised Adivasi community, Gond art plays a powerful role in voicing the stories of oppression and activism in ‘Bhimayana’.

The cover of ‘Water’ showing a boy with an ‘untouchable’ hand and fish that try aiming at a well, placed in the distant sky, speaks fathoms of his social struggle. When Ambedkar addressed thousands of Dalit persons at the Mahad Satyagraha to fight for drinking water from Chavadar Tank, the art converted his speakers into tiny sprinklers of water signifying the worth of the movement. To me, Bhimayana spoke for the pain every Dalit has suffered through Ambedkar’s eyes. While it narrates the emergence of extraordinary anti-caste movement, it doesn’t stop throwing little drops of irony just when the reader stops expecting them.

The present-day casteist atrocities in many news reports found in the novel range among individuals being beaten up, kicked out by their landlords, sexually harassed, and even murdered. Countering a common caste Hindu argument that caste may not exist in urban areas and is a thing of the past, the narrative repeatedly reminds the readers that caste has never been dead after all.

Rohith Vemula, a Dalit student and PhD candidate’s unresolved culpable homicide in 2016 screams the intensity of the caste prejudice in India and Vemula’s writings, particularly on his Facebook (now converted into a book), alarmingly reminds the same. Rohith often wrote that caste is not a rumour and Bhimayana helps you unfold both Rohith’s death as well as his anti-caste opinions.The irony of the narrative becomes even more relevant today as another anti-caste advocate, Anand Teltumbde had been asked to surrender on Ambedkar Jayanti, after being accused of ‘triggering violence in Bhima Koregaon’ in January 2018 by the Pune police.

After Ambedkar’s century-old resistance, Teltumbde’s arrest is a painful warning to all minority communities in India against raising voices and demanding equality. Whether we talk about Ambedkar then or Teltumbde now, stories of Dalit oppression and resistance are always forgotten. M.K. Gandhi’s Satyagraha receiving more public support over Ambedkar’s resistance in Mahad validates the one-dimensional history that we know today. Bhimayana shows the underrepresented history of India’s struggle for freedom, adding several other layers of timelines to our history textbooks.

Also read: Where do I Place Ambedkar at My Home?

While Gandhi’s struggle was for freeing India from foreign prejudice, Ambedkar aimed at resolving discrimination within the country and transforming the Hindu society. Gandhi’s first experience with discrimination in South Africa happened far from the social security he had received in India — something that Ambedkar had already experienced when he was young.

Our upper-caste society never seems to get out of its saviour complex. When Ambedkar wanted to represent untouchables, Gandhi derailed the process with the idea of independent electorates as he claimed, the untouchables weren’t ready to save them against themselves. Today, almost 90 years later, we still find its glimpses creating many privileged dialogues, one of which is in the film Article 15. While the movie allegedly aimed at depicting the struggles of marginalised castes, the protagonist remained a privileged, Brahmin police officer fighting anti-caste battles, thus conditioning the viewers that an ‘untouchable’ can never be worthy of leading a movement even if it is made of their own traumatic experiences. Bhimayana, using an evidence-based approach, shows that the inclusiveness in the constitution of our country is based on Ambedkar’s experiences as a Dalit and if the constitution was drafted by someone else, particularly a caste Hindu individual, things would have been different today.

Being introduced to Bhimayana as a 17-year-old student, I have always wondered how my political viewpoints would shape if I read this when I was younger. Our textbooks have always shown histories and politics that are convenient to convey or are overshadowed by dominant communities in India. We have grown up reading about resistances against Britishers and Mughals or jargon about equality among all people in India without truly understanding what equality means and how it varies among different communities.

How do we connect these dots to guide our students with a more unbiased, intersectional approach to understand our society? How do we ensure that over 10,000 Dalits coming together to burn Manusmriti also finds its way in mainstream textbooks — a revolution that is important to understand social inequality in India? Bhimayana, while dealing with these issues, provides a more holistic connection between the past and present and compels the readers to get over their biases. Due to its beautiful art and the simplicity of points that it makes, the narrative can be a good read for both adults and children.

Bhimayana is a constant reminder of the age-old casteism enveloping our society. It simplifies Ambedkar’s intention behind politicising untouchables and fighting for anti-caste rights independently without relying on the kindness of caste Hindus and feeding their saviour complex — which has given birth to so many anti-caste alliances and movements today.

Bhimayana, though a simple read, challenges us to think beyond the narratives that we have been spoon-fed with and tells us why the missing pieces of our great Indian puzzle are relevant to what is happening to us as a society. The narrative ends with the Dalit woman and the caste Hindu man boarding the bus together — the same bus which had persuaded Ambedkar to hide his caste identity — the bus that remains a prominent symbol of the contribution that the anti-caste movement in India has given us.

Ayushree is a writer who makes books for children at Katha. Some of her writings have appeared in Outlook India, The Times of India, Newsd, and more.

Featured image credit: Wikipedia/Editing: LiveWire