Filmmaker Satyajit Ray had felt chastened by the city of Banaras (also spelt Benaras or Varanasi). An ineffable quality, a haunting charm wafting through India’s oldest city (and one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities on Earth) had mesmerised Ray, a feeling that was perhaps both transformative and transcendental.

It was while watching Ray’s Joy Baba Felunath (1979) that author Nilosree Biswas had her first encounter with Banaras, although she had to wait another two decades before she could sample the city first hand.

Banaras, believed to have been brought into being by the meditative intensity of Shiva, who had subsequently vowed never to desert it, appealed to Biswas with a “fervent fascination”. She could see how the holiest place in India revolved around the same cycle of interactions between humans and Gods as the great Greco-Roman plays that interlaced desire, defiance and destiny.

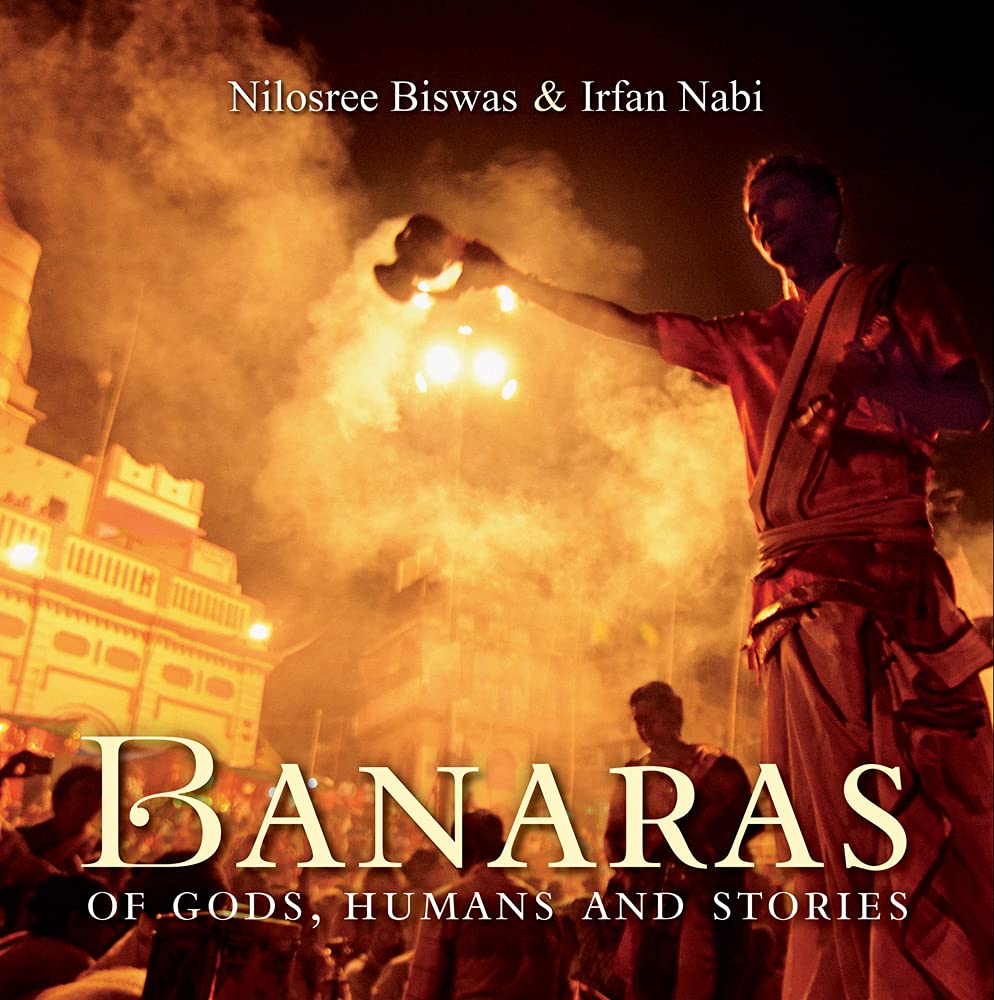

Banaras: Of Gods, Humans and Stories

Nilosree Biswas and Irfan Nabi

Niyogi Books (June 2021)

In October 2017, Biswas formally began the process of documenting Banaras, in tandem with photographer Irfan Nabi. The two had previously collaborated on Alluring Kashmir: The Inner Spirit, a nuanced look at how the Valley is so much more than ethereal sceneries and ugly politics. In Banaras: Of Gods, Humans and Stories, published by Niyogi Books in June, Biswas and Nabi pay their tributes to a place whose landscape and mindscape fuse into one. A place where the boundaries between the exterior and the interior, the physical and the metaphysical, blur seamlessly.

The difficulties of writing about Banaras are obvious. A certain timelessness pervades the city, not unlike other ancient cities such as Rome, Cairo, Jerusalem or Istanbul. A timelessness that, in the words of Biswas, is like a “dice made of many overlapping ingredients, including mythology, fables, patrons, traders, chroniclers, the nameless pilgrims, and the emperors”.

In Banaras, too many stories lurk at the bend of a gali, at the precipice of the ghats, at the juncture where a motorbike grazes the skin of some cattle as a pair of lovers look on, temporarily distracted from their kachoris. To distill these narratives and contextualise them within the complex contours of Banaras’ socio-political history requires a dexterity that only comes with fully embracing one’s subject. Biswas and Nabi embrace Banaras quietly yet completely, writing with languorous lucidity and capturing the city with precision and stillness.

Banaras does not read like a conventional travelogue and nor does it resemble the kind of biography where a city is championed and traced chronologically, similar to the treatment reserved for Dickensian protagonists in a Bildungsroman. Instead, Banaras involves a visceral and sensuous mapping of the components of civilisation – religion, architecture, food, entertainment, more food and music, to name a few – that animate the city. It is this approach to project Banaras through the five senses (one is tempted to add a sixth, that of spirituality) that makes this book a richer and more genuine reflection of Banaras than any over-budgeted 4K documentary.

There are the expected accounts of Banaras’ incredible mythological roots, of how Shiva and the river Ganga, between them, imbue Banaras with a larger-than-life character. In fact, an entire chapter is dedicated to Ganga or the Ganges, which is described as an “endless source of sacred water, a purifier, a bountiful mother, an epitome of energy, and also Shakti, the saviour, in liquid form”.

There are detailed retellings of how Banaras has journeyed from antiquity to urbanity, from the magnanimity of Akbar to the malfeasance of the British to the mishmash of power and passion that has underlined the city since India’s independence. This is where an outsider gets a distinct flavour of spots like Kashi Khsetra (the most dwelled part of the city), the Chowk (the commercial hub), and the renowned Kashi Vishwanath temple whose genealogy is covered extensively. The city’s geography comes across vividly as “a perfect mandala, a round configuration with a clear central point”.

There are also plenty of conversations, intimate yet (largely) unbiased, with silk weavers, paan sellers, craftsmen, erstwhile pehalwans, and many more. Their words dovetail with Biswas’s own to encapsulate “Banarasipan”, the timeless zeitgeist of Banaras:

Banarasipan is existential in its nature. It is a life choice, freewheeling, that stems from historical and religious currency, but is not the only gage. It is more about the informed social behaviour, consisting of everyday activities, reflected through the way of life, embedded in the veracity of people. Banarasipan is an adjective, a leveller in its notion, and in literal — that which omits the divides of religion, class, caste, etc., something to the effect of being addressed as universal, that is, ‘all of Banaras’.

There was a time when ivory, apes and peacocks were exported from Banaras to the palace of Solomon, when the silks from the city landed in the wardrobes of ladies in Versailles, when ships sailed across the Ganga ferrying Muslins from Bengal, jewels from Golconda and shawls from Kashmir, all destined for St James’s Court in the United Kingdom. Those days are no more, but Banaras still retains its share of grandeur. A grandeur that relies less on opulence and more on authenticity, on projecting humanity against the greater tapestry of life.

The image of a solitary figure lighting the steps of the Manikarnika kund, a well submerged in antiquity, during the occasion of Diwali makes for a spellbinding sight. The contrast with its preceding image, a monochrome shot of an elderly person fetching water, is unmissable. The pictures, as always with Nabi, weave their own sub plots, complementing as well as challenging Biswas’s text to probe deeper into the sacred heart of Banaras.

Also read: Shashi Tharoor’s New Book Is Broad and Brilliant, but Not Bold Enough

In the second half, the book deftly manoeuvres its themes to present one of the most intriguing binaries of Banaras – the tango between death and pleasure. The cremation ghats of Banaras, particularly the Manikarnika ghat, are depicted with an ease and grace that tames the menace of earthly exits. Death is seen not merely as an inevitability, but as a source of assurance; as a suitor who stops to guide one from this world to the next. In the larger context of Banaras, death is just the final step in the lifelong quest for pleasure, which, having satiated the impulses of the body and the mind, must end by quenching the soul.

This quest is facilitated by a device that would be familiar to those acquainted with the literary prototype of the flâneur – a person who saunters around observing society. A flâneur, safe to say, would not be out of place in Banaras, engaging with the all-important device of wandering, an act unique to Banaras, which blurs “the distinction home and the notion of home being the ultimate space of comfort”.

Banaras undoubtedly does justice to the material as well as the supernatural aspects of a city that is, in so many ways, the perfect example of a sui generis space. Yet, Banaras leaves the reader tantalised, even tense, by dangling the political threads of the city without deconstructing them. Consider, for instance, the following passage:

Banaras is considered as a brand of irrevocable importance – it is premium, incomparable with any other city in India, and one that encapsulates the core concept of majoritarian Hindu theology and its universe.

After rightly pointing out the imperative role of Banaras in shaping the Hindu ecosystem, the book makes no attempt to engage with its political connotations.

Also read: What an Old Man at Assi Ghat in Banaras Taught Me About Life

Does the rising tide of majoritarianism in Indian politics and the deformation of Hinduism into Hindutva not affect the sanctity of Banaras? How exactly, if at all, can Banaras’ sublime religiosity counteract communalisation and preserve the secular undertows of Indian society? Why did Narendra Modi choose Banaras as his constituency for the 2014 and 2019 general elections?

Banaras does not show any interest in grappling with these questions.

In fairness to Biswas and Nabi, they never mention the relationship between Banaras and contemporary politics as part of their mandate. They are, of course, entitled to conceive of the city as they please, but for readers wishing to understand the role of Banaras in the India of today, there is room to be marginally disappointed, to feel that an opportunity for an important conversation has been lost.

Historian William Dalrymple has labelled Banaras “as an affectionate love-letter to the holiest of Indian cities”. The book is certainly that and so much more, even if it may not be “the perfect mandala”.

In the spirit of the city that it captures with so much care and concern, Banaras is in parts gentle and glaring, inundated with the quotidian and the queer. If one is to look for an enduring message in a work that makes no pretensions to pontificate, one would do well to find solace in the following:

Banaras [is] a nectar pot that is filled with flavours, not always honeyed, but many times tangerine.

Priyam Marik is a post-graduate student of journalism at the University of Sussex, United Kingdom.

Featured image credit: Pariplab Chakraborty