I write this as I glance over the newly-released Haruki Murakami diary launched by Penguin for 2020. To start a new decade with the writer’s words, which are all about eclectic solitude, seems about right.

But these words are not so easily describable. Recently, when I was talking to a friend about her favourite writer, she said something very interesting about how difficult it is to pen down how she feels about that writer: How can one adequately give justice to a writer through words – someone whose work has literally moved you to understanding the very essence of the written word?

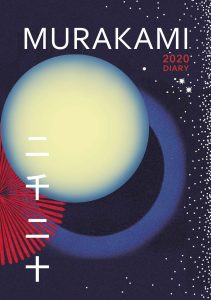

Murakami 2020 diary. Photo: Penguin

Murakami is by far one of my favourite writers, one whose quotes I rely on to get perspective; whose characters have taught me so much over time, with patience. However, I too can’t possibly write about the author and feel adequately satiated with the response that flows onto paper. Instead, what I can do is take his help in understanding what the writer made me believe in.

Taking a cue from his book, Novelist As a Vocation, I will try to understand ‘Murakami As a Vocation’.

My first book of Murakami’s was South of the Border, West of the Sun, a story of extreme regrets that featured Hajime and Shimamoto as the lead characters. The book, for someone who was stuck in a vortex of idealism, gave new meaning to making mistakes; that it’s okay to make a mistake and seek redemption, even though the mistake truly and terrifically broke someone.

Nothing that you could do, no dark thought you could have, is beyond redemption.

So when Hajime chronicled his life – as a child, as an adolescent, as an adult – it was laced with bad choices, riddled with complete and utter misguidedness. Yet, he had a self-assuredness about himself. So when he was at the precipice of enabling someone to make a choice that was thoroughly myopic – he gleaned under perception.

This is what Murakami’s writing was all about – you fall deeper into a well, but believe that you will come out a better person.

Not that any Murakami book is bad, but my personal pet-peeve is with people calling themselves fans of the writer despite only having read Kafka on the Shore and/or Norwegian Wood. Both books evoke the familiarity other books by the writer have, but make the audience believe that loneliness and love are the winning elements of the writer when in fact, the writer was about messing it good, really good – and yet acknowledging it, and still living with it.

His book Colourless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage is a perfect example; Tazaki had broken a relationship dynamic so significantly that in a perfect world, especially one crafted in literature, the schism was almost too tragic to relive – but the titular protagonist lived on. Moved on. But not by the guise of forgetting it, no, it’s by knowing that your biggest mistake, in fact, lives with you on a daily basis. Tsukuru’s ability and his simultaneous emotional disintegration made me, or any reader, believe in the destiny we have chosen for ourselves vis a vis significant non-conformist choices.

“If nothing else, you need to remember that. You can’t erase history, or change it. It would be like destroying yourself.”

My first few Murakami books, especially my third-favourite, Dance Dance Dance, brought me to the forefront of magic realism – the genre that Murakami ascribed to. The genre that gave birth to the infamous Murakami bingo game, with the talking cat, the sheep man, the weird surreal aberrations that everyone underwent at the Dolphin hotel. The genre that we got a glimpse of in his recent The Strange Library, and in the short stories – ‘Birthday Girl’ and ‘Samsa in Love’. The genre that I witnessed first-hand during my trip to Tokyo when I wanted to map out the places he wrote about, he spends time in, he thinks in. While trying to be Sumiere in Inokashira Park was easy, going to his favourite haunt – The Lion Bar was not at all easy. Everyone knew it existed, everyone knew its surroundings, but no one got to know where it exactly rested.

So when I spoke to a few locals, my best friend and I were told that it nestles in an alleyway around Shibuya, and the map can you take till a particular location, after that you are on your own. We did exactly that. The story of the Lion café was completely out of a Murakami book – the place was a silent café, with milk and other milk drinks on the menu, the seats were stacked one behind the other, the only voice you heard was when the musician changed the vinyl record from one jazz to another jazz song.

I remember vividly discussing with my friend via text how utterly eerie it was. But people revelled in its hurried quietness. They were sitting with their notebooks, staring into space and just musing over the music.

Murakami’s words make it okay to be worried, to be scared, to cry, to prod, to ask questions, to express negative emotions without worrying about showing off your weaknesses. It is only when you truly live with your misgivings do you believe in the idea of living with your joys. Murakami’s contribution to literature isn’t just about the cultural significance it held – that is a mere part of it.

Of course, the cultural relevance and pertinence of the books holds true, his non-fiction shedding light on fatal devastations, on music, on cooking, on running. But the more important lesson he provides lovers of literature is to those of us who have been inspired by him to write. Interpersonal relations needed to be nurtured and harvested, but not before one established a relationship with their own self. Away from prejudices that we had for what believed in, away from the second guesses we alluded to our own ideas, away from the misconceived bias we had about ourselves that manifested into complexes.

His words enable the writer in me to write every thought I had, good or bad, made me believe in opinions that I had whether well voiced or not, I could just as easily prepare an entire world based on my intuition and defend its existence.

Murakami is that reader who looked at his characters as novelists he adored, he is that writer who understands the litany and procedural accuracy of non-fiction that is pragmatically sad, he is that music lover who comes on the radio as a DJ to tell you all about his music, he is that chef who walks the talk when it comes to his food akin to his characters, he is that literary force who believed in the trepidations of a road full of imperfections and treat them as that and not sugar coat them, but just accept them, whether they are yours or they are someone else’s.

Shiralie Chaturvedi is a writer who loves Murakami and Seth; indie cinema and bands; cries listening to patriotic songs, and is happiest at home with her loved ones.

Featured photo: Scanpix Denmark/Henning Bagger/via Reuters/File Photo