‘He is not dead. There is still life left in him.’

‘O leave it, my friend, I am exhausted.’

– Resting Time, Sadat Hassan Manto

Exhausted. That’s how many of us have been feeling lately.

This isn’t something that only those part of the anti-Citizenship Amendment Act protests are feeling, or those devastated by the recent bloodbath in Northeast Delhi. Or perhaps, even the pro-CAA contingent and the police personnel.

As Indians, we are all writhing in anger, anxiety and maybe a certain sense of unending anguish, worrying about where we are headed at the start of a new decade.

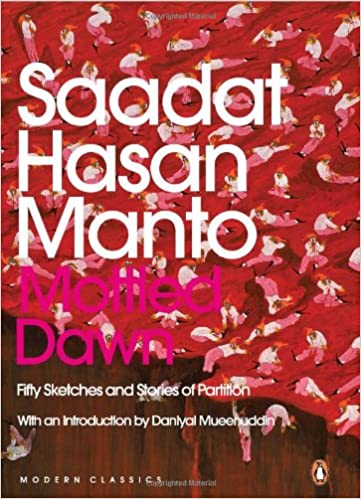

Mottled Dawn

Saadat Hasan Manto

This emotional state is a common theme in Saadat Hasan Manto’s book Mottled Dawn. The book consists of numerous short stories besides sketches as short as the two lines mentioned above – each hitting a hammer blow to readers about the horrors and trauma of Partition. The stories are about people who woke up one day to find intruders in a land which refused to recognise them as its citizens.

With the introduction of the CAA and the National Register Citizens, the horrors of Partition have resurfaced. When the Bill was tabled in parliament, millions were suddenly made to feel alienated in a secular Indian Republic.

One can feel this heightened sense of alienation throughout the book, a sense of estrangement which Manto experienced during the Partition as well as in his latter part of life in Pakistan, where and when he penned his most influential anecdotes.

In the story ‘The Dutiful Daughter’, a mother is desperately looking for her daughter after they get separated during Partition. The mother, refusing to take help from the police, almost goes insane while searching for her child. Year later, fate brings them together when the daughter’s husband catches a glimpse of the mother while crossing a road and tells his wife that he saw her mother.

Manto then writes –

The girl looked up, but only for a second. Then, covering her face with her chaddar, she grabbed her companion’s arm and said, “Let’s get away from here.”

The mother recognised her daughter and screamed out her name with the utmost surety while the husband and wife walked away “taking long, brisk steps.” A policeman then caught hold of her. Seeing a delirious woman shouting, he said that her daughter was dead. The mother then “fell in a heap on the road.”

This sense of disbelief, shock, and despair was what millions in India felt when the CAA was passed in both the houses of the parliament. In the present context, the daughter can be compared to the ruling government and the mother to the numerous grieving Indians, who were suddenly made to feel abandoned, and neglected by someone who thought were their own.

Also read: My Grandfather’s Bedtime Tale of Tolerance

This element of shock and awe starkly reflects in other characters in the book. In the story ‘The Assignment’, the son of an age-old friend of a family comes to deliver a package during the riots. Initially, the family keeps the doors locked for their safety but they open the door after seeing him standing outside.

He hands over the package as rioters ran towards their house with “cans of kerosene oil and explosives.”

In words of Manto –

One of them asked Santokh (the son), ‘Sardarji, have you completed your assignment?”

The young man nodded.

‘Should we then proceed with ours?’ he (a rioter) asked.

‘If you like,’ he replied and walked away.

Manto did not hold back. He wrote and mentally framed the stories and their characters, as was his surrounding. He showed us a world which was equally, if not more, apathetic.

Khalid Hassan, the translator (who has translated works of Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Ghulam Abbas) of the book, gave an eerie analogy while talking about Manto’s work.

He said that the Partition of 1947 was more horrific than the Holocaust. In the latter, the state (Third Reich) was responsible for the extermination of the Jews. In the former [1947], he wrote, “something snapped”. People belonging to a civilised society, who lived cohesively and peacefully together, suddenly turned into a rabid maniacs perpetrating unspeakable acts on each other with rampant retaliation from both sides.

Again, in the current context, are we not seeing something similar in the Delhi pogrom?

As Indians, some of whom are still blinded by the pride of living in the “world’s largest democracy” or Donald Trump’s visit to India, Manto’s Mottled Dawn is, and perhaps will be, a disturbing but necessary eye-opener to identify the hidden demons which are feeding on communalism, bigotry and divisive politics.

Manto’s own words remain true as ever: “…and it is also possible, that Saadat Hasan dies, but Manto remains alive.”

Ayushman Basu is a marketer by profession with dreams of becoming a musician one day. Even if the album might not be a hit, it will strike a chord with some people.