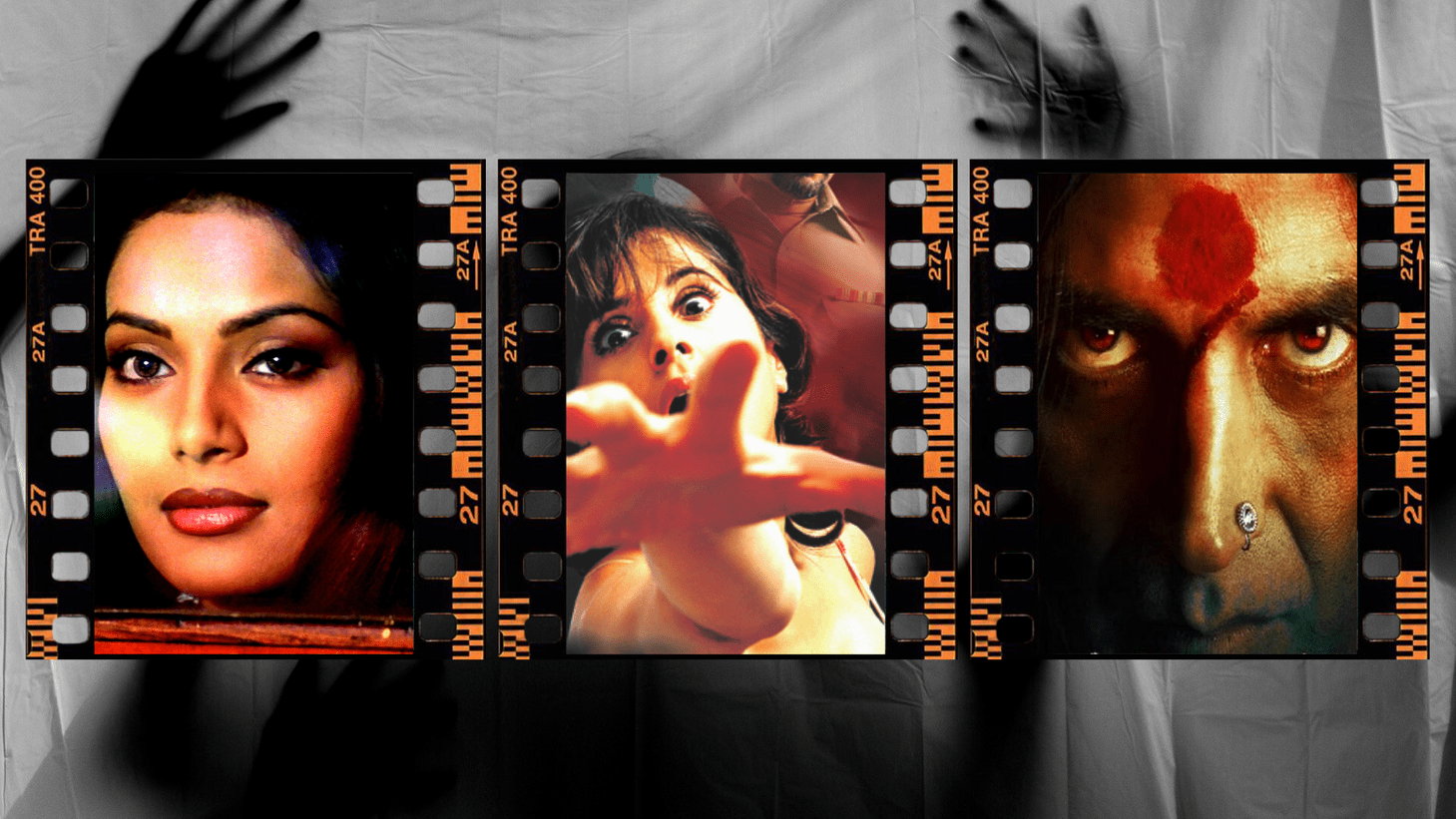

Horror films, except for a few like Bulbbul and Stree in recent times, have always been deeply misogynistic in portraying evil, avenging, disgruntled spirits of dead women having come back to exact revenge.

Examples of such films include Raaz, Raat, Alone, Bhoot and Raagini MMS. In all these films, the supernatural and repulsive female subject is invested with the deepest and darkest qualities imaginable; her being and persona are both a projection of deep-rooted patriarchal anxiety of women. The whole narrative is mobilised to oust this horrid spirit, however just her cause may be. In Raaz (2002), for instance, the avenging spirit is a wronged woman. Yet, the chaste and devoted wife of the man who had claimed to love her and was instrumental in her death, moves heaven and earth to save her husband from the spirit.

Women in horror films

The ultimate success of such horror films is in the thorough and utter destruction of the “evil” spirit, who, by virtue of being dead, has by default become evil while her wrongdoers enjoy our sympathies as they are mortal. The same revenge narrative however takes the form of a hero’s journey when the protagonist is a man and a mortal and leads to blockbusters like Sholay, Akhree Raasta and Bahubali 2 that glorify the wronged hero’s revenge and the destruction of the wrongdoer.

Most of the time when the spirit is that of a dead woman – as in the case of the above mentioned films – or if it plays through, manifests in or attacks another woman, it just becomes so much more pleasurable as in the case of films like 1920, Raaz 2, Hawaa and even Bhool Bhulaiya.

Also read: The ‘Chudail’ Archetype Is the Personification of Society’s Fear of Assertive Women

Male bodies playing spirits or spirits playing through bodies other than those of women are somehow far less compelling. This constant exploitation and spectacle of the female body in the horror genre is a way of otherising and pathologising the woman through a misogynistic patriarchal gaze and projecting man’s ultimate fantasies and fears on her persona.

In The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir analyses the construct of the muse supposed to inspire poets and artists, as an instance of man’s projection of his ultimate fantasies onto a woman. The same applies to the construct of goddesses especially, those like the Indian Kali and the Matrkas, the Aztec Coatliciu, the Russian Rha, The Cretan Rhea and the Nordic Valkyries who symbolise the polar opposites of life and death at once in their persona.

Laxmii

In the recently released horror comedy film Laxmii, misogyny and transphobia come together and are projected on a Muslim male body. It is interesting how all three demographics are objectified in the film. The women in the film are caricatured when they try to exorcise the ghost, while the cisgender Muslim man Asif is trapped in the trope of the apologetic Muslim for having married a Hindu girl. There are deep rifts between the family members’ positions on the issue of the Hindu-Muslim marriage, with the Hindu patriarch of the family having disowned his daughter.

Ironically, all members are united and this rift is undermined by the family’s common and collective transphobia. The terror, the shame and the embarrassment that each member of the Hindu family experiences when they see their cisgender Muslim son-in-law suddenly becoming gender-queer – effeminate in common parlance and the amplification of this fear through the heteronormative and cisgender gaze of each family member establishes that transphobia is much bigger than Islamophobia and it is ultimately fear and not love that is the biggest unifying factor. This dread manifests itself long before the family has even concluded that Asif may be possessed by a spirit.

Also read: ‘Laxmii’ Is Cliched, Mediocre and Offensive, All at Once

Despite going into the sad story of the disgruntled and wronged trans woman’s spirit which has taken hold over Asif’s body, the film only succeeds in briefly humanising transpersons and eventually ends up pathologising them and in fact even elevating the common, shared fear of the heteronormative community towards transpersons. It makes frequent attempts to somehow mythicise and thereby otherise the “kinnars” by way of recurring iterations that imply how it is an unforgivable sin to oppress or mete unfair treatment to trans women. Does that mean that it is okay to oppress other marginalised demographics since there is no pronounced edict?

Caricatured songs

The film has a song which is supposed to show some kind of celebration and festival observed by trans women. The number is loud, the music unrelatable and the whole song is reminiscent of the song and dance sequences sometimes found in the films of the 90s that would caricaturise tribals by presenting them as wearing skirts of leaves and flowers, making ululating sounds and body movements which stood out in sharp and uncomfortable relief against very urban, neoliberal and modern spaces.

There are numerous Bollywood songs which use the setting and context of festivities – for instance, ‘Dola Re Dola‘ in Devdas, ‘Pinga‘ in Bajirao Mastani, and hypermasculine numbers like the malhari dance in Bajirao Mastani, all of which are intended to inspire awe and admiration. However, the song and dance sequences that have Saif Ali Khan in Tanhaji, the ‘Khalibali’ song portraying Ranveer Singh in Padmaavat and the ‘BamBholle’ dance of Akshay Kumar in Laxmii add to Islamophobia (in the first two instances and transphobia in the third instance) instead of generating awe and admiration.

The song-dance sequences offer these communities as a spectacle, as manifestations of the object which becomes a source of perverse pleasure for the viewer-consumer. This has a lot to do with subliminal, audio-visual and spatial cues that typecast the characters and the community portrayed in the song according to hegemonic ideas of representation, thereby alienating them further and reinforcing mainstream perception of them.

‘Passive wife’

Laxmii also inadvertently ends up normalising misogyny and sexism and stereotyping gender roles whether it is in the refrain which Asif uses time and again to show his utter disbelief in the supernatural world: “Ma kasam agar bhoot woot kuch hota hai toh mai chudiyan pehen loonga (I swear if there are ghosts, I’ll start wearing bangles)” implying that wearing a woman’s accessory is the ultimate humiliating action a man can inflict on himself (prematurely revealing his transphobia), or in Rashmi’s assurance to her father about her husband, “woh mujhe bahut khush rakhta hai (he keeps me very happy)” entrenching the man’s role as provider and protector, to showing Ashwini, the daughter-in-law of the family waiting at the table while everyone else is eating.

It is true that the film does engage in some kind of a visibility politics through a positive representation of Laxmii’s Muslim foster father and his disabled son, but these characters are purely unidimensional just like the “stupid” women and the “passive wife” tropes and are a little more than props to foreground Laxmii. Laxmii’s ululation, the strange inhuman gritting noise she makes by grinding her teeth which manifest in Asif through her spirit, her threat to kill the family members of the Muslim seer’s followers who have come to exorcise her, are subliminal elements that demonise her and through her, the transgender community, normative heteropatriarchal society knows so little about.

The film Laxmii can be lauded for marginally visibilising the transgender community but sadly ends up dehumanising trans women more than giving them and their predicaments voice and screen space.

Dr. Shyaonti Talwar is an academician, researcher and a writer whose areas of interest include art, culture, lifestyle, social inequality, literature, mythology and gender.

Featured image credit: Nick Magwood/Pixabay; Illustration: LiveWire