A friend recently explained how Snapchat works, and I remember feeling slightly disconcerted. I learned that streaks are an integral part of Snapchat — you and your online friend have to send each other a Snap at least three days in a row to maintain it. These Snapstreaks come to signal the seriousness of the friendship. As the numbers increase, you feel a sense of accomplishment on having obtained a BFF, while the breaking of the streak indicates the end of the friendship itself.

The snap, meanwhile, lasts only for five seconds until it disappears forever.

What struck me, while my friend was explaining this, is the app’s focus on a very private act of photo sharing but also on the ephemeral nature of it. The intimacy it is trying to forge between two people through the instant sharing of some minuscule part of their lives, which is bathed in performance, possible deception, and a heavy filter, felt inconsistent, if also not inherently contradictory.

Thinkers like Nietzsche or Foucault have always talked about power as a central driving force in humans, an ever-present element in any inter-personal relationship. For me, intimacy, then, becomes a sacred space, a reach across social structures and falsehood in the world to create something real with another human being. Garth Greenwell spoke of intimacy as encountering some sort of “human surplus” in the space between — it is not about two people but what is formed between them.

Intimacy is often born from the yearning for human connection which exists everywhere because it speaks to us about our existence that is fraught with terrifying, primal, ethereal and ambiguous moments — and a sense of closeness with the other, helps us to find the right note in the cacophony of the universe.

It seems to me that in modern culture, we crave intimacy as much as fear it. Perhaps because it requires dispensing with barriers we have set up for ourselves and exist in a state of nakedness, undressing, stripping away. Author Sally Rooney depicts this new-age, modern intimacy in her debut novel Conversations with Friends. The protagonist Frances falls in love with a married actor Nick and the frustration and misunderstandings that ensue between the two is partly a result of their inability to properly accept, receive and provide intimacy.

Also read: Love and Self-Loathing in Sally Rooney’s ‘Conversations With Friends’

Rooney’s characters belong to an educated class and are often theorising their own feeling, articulating about the world and the philosophers they have read about, but the language seems to escape them when talking about their own feelings. At one moment, Frances tells Nick very coldly, “I just don’t have feelings concerning whether you fuck your wife or not. It’s not an emotive topic for me”, but later her hurting herself proves otherwise. At another time, she blurts out that she loves Nick in front of him, and he asks her to stop being “over-dramatic”. Their intimacy, however, unfolds when they are having sex, experiencing that closeness which they have to hide from everyone else, even from their own selves at times.

The pandemic and endless lockdowns have made me quite aware of the importance of daily intimacies and the bulk of them which we have lost. The idea of standing two meters away from your close ones, exposed to emotions but unable to touch, intensified the sense of isolation and alienation for most of us. One would think that distance will bring us closer, allow us to be able to better apprehend the human connection through the gap but Byung-Chul Han, in her essay ‘The Tiredness Virus’, talks about the disappearance of the other itself during lockdowns. She contends that we are experiencing persistent fatigue during the pandemic because we are constantly confronting ourselves, thinking and speculating about our being: “Other people, who could distract us from our ego, are missing. We tire because of the lack of social contact, of hugs, of bodily touch. Under quarantine conditions, we begin to realise that perhaps other people are not “hell,” as Sartre wrote in No Exit, “but healing.”

Also read: What Will Our Relationships Be Like When All of This Ends?

It is important to focus on the rebuilding of the economy once the pandemic ends but what about the culture of intimacy?

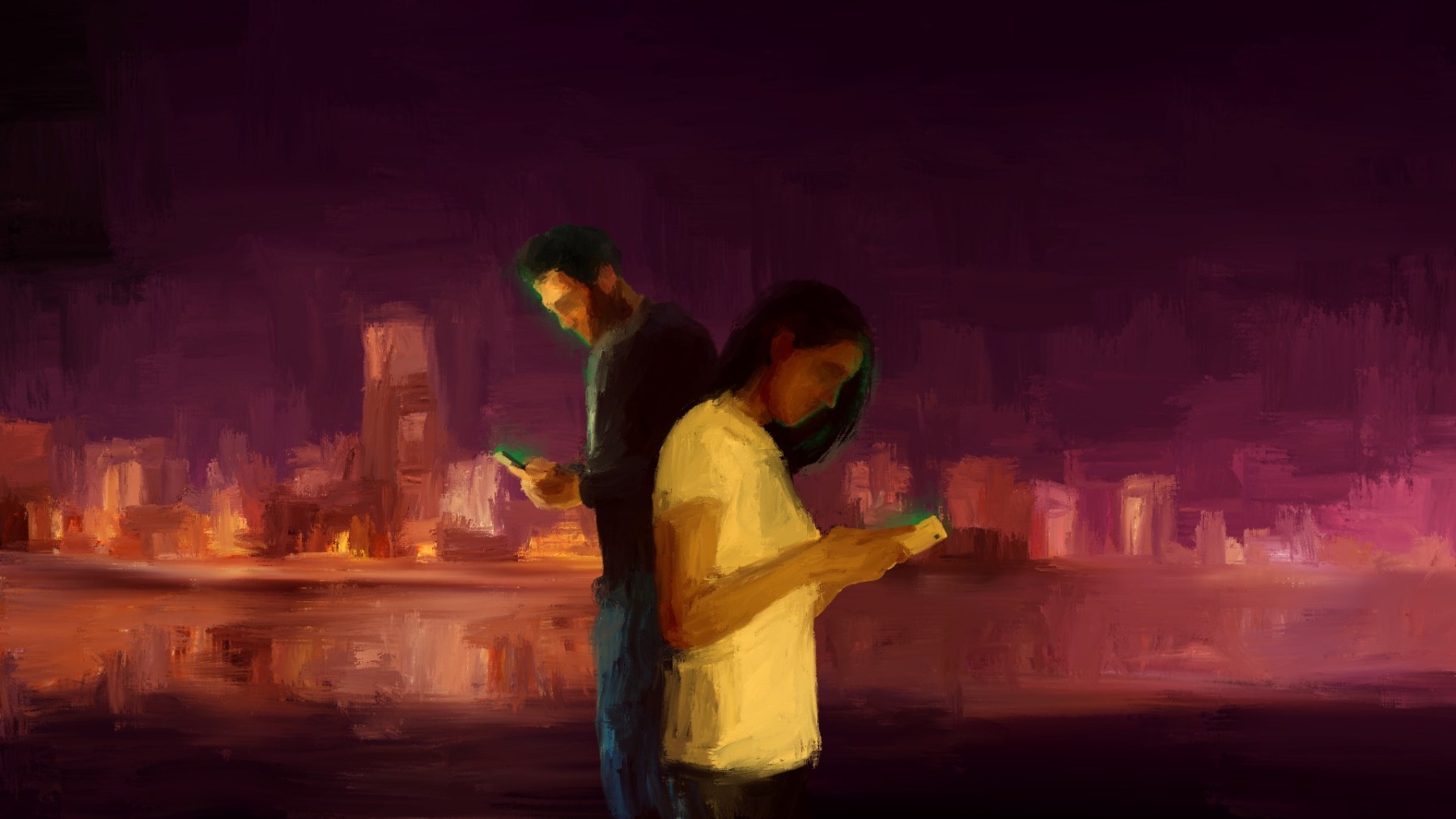

There are different ways of creating intimacy, and as the pandemic is teaching us, we are creating and maintaining intimacies through texts, video chats, social media, and the likes of it. When held up to physical intimacy, online intimacy can feel fundamentally inadequate. And perhaps it is. Online communication is often a one-sided affair. There is no random or accidental touch of the other, no eyes gazing back at you closely. Communities and rituals are significant ways of creating intimacies, that reminds us how our existence deeply relies upon the presence of the other. Online communication, on the other hand, consumes us until we are the only ones we are left with.

Our online realities become eerily identical in nature until we become clones of each other, slaves to the algorithm of the internet. The connection remains unresolved, unsatisfying. Philosopher Zizek, in his essay ‘Sex, Love, and Coronavirus’, quotes Arseny Tarkovsky: “A soul is sinful without a body,/like a body without clothes,” highlighting the significance of intimate bodily contact. The virus doesn’t allow us to be intimate with others, in effect, alienating us from our own bodies.

Does this way of thinking reduce intimacy merely to physical touch?

Intimacy is about connection and it can happen anywhere, whether on a text or in a cafe. In Poetry in Painting, Helene Cixous wrote about dealing with something real even without any bodily contact: “there are many ways of touching without touching, without touching be touched, to be in the continuity of the real.” Should we stop viewing online interactions with suspicion? Do the way we connect has really changed? Is it time to stop discarding digital intimacy as a lesser version of the physical one and accept that real friendships can be forged in a world where texts and video chats are our only ways of contact at the moment?

Shanna is currently pursuing her Masters in English Literature from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

Featured image credit: Pariplab Chakraborty