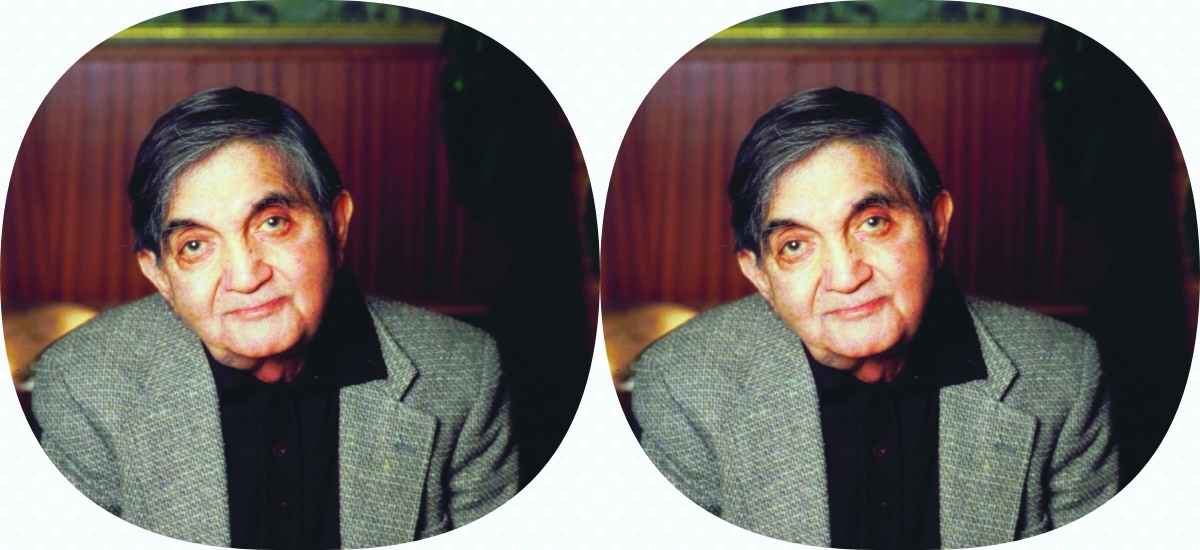

Vineet Gill’s recently-published book Here and Hereafter: Nirmal Verma’s Life in Literature recognises Nirmal Verma as one of the greatest writers of 20th century India who wrote, unlike Salman Rushdie and Arundhati Roy, in Hindi. Perhaps, it was this choice of language that limited the circulation and appreciation of his work. Yet, Nirmal Verma’s writing was never limited to a regional or even a national identity. His first novel Ve Din was set in Prague and is the first Hindi novel to be set entirely in a western country.

Gill acknowledges this universal tendency in Verma’s work and begins his book with the phrase “World Literature”. Verma’s life records a journey across various cultures, and there is both a physical and psychological aspect to this journey. Physically, Verma travelled across various parts of the Europe and wrote about it in his novels, memoirs and essays. Psychologically, Verma travelled through the act of reading as he engaged with a diverse kind of world literature by translating it into Hindi and analysing it in his essays. These two journeys transform him into a writer who is truly a part of world literature.

Here and Hereafter: Nirmal Verma’s Life in Literature

Vineet Gill

Vintage Books (September 2022)

The world here is not a unified whole, but a series of fragments: memories, influences and experiences gathered from disparate sources from adventures in Iceland to the reading of Czech and Russian writers. Verma transforms this collage of disparate, disjointed fragments into his unique literary voice.

Vineet Gill’s Style

The book offers a close reading of Verma’s works with chapters focussing thematically on death, travelling, critical writing, and on cities that appear in Verma’s fiction such as Delhi, Shimla and Prague.

One chapter is about Verma’s memoirs about his travels across Europe. Travelling was central to Verma’s “creative practice — his body of work was simply an offshoot, a by-product of all the journeys he’d made”.

In Verma, there is a sense of traveller’s wonder and awe about the West, but it is always combined with the analysis of an insider. As Gill mentions, “Verma travelled, and wrote about his travels, like a flaneur, but with always an eye on historical currents.”

Verma was proficient in European history and its literature and, therefore, combined his knowledge and information with the observations of an outsider. For instance, in an essay titled “Brecht and a Sad City” he looks at the different political structure and consumption patterns of East and West Berlin with the eyes of a journalist observing the grand currents of history in the anecdotes of everyday life.

Gill writes his book with a unique style that combines memoir, biography and criticism. For instance, the second chapter explores death in three distinct ways. It begins with Verma’s death as he lay in AIIMS hospital suffering from colon cancer during his last days. It combines this with Gill’s own obsession with death while reading literature. (“My handwritten notes on the back pages of the books I have finished… invariably carry the word—Death”). And, it traces the presence of death in Verma’s work from his first short story collection Parinde (1959) to his last novel Antim Aranya (2003). Thus, the chapter offers a blend of biographical details, literary criticism and personal memories.

The question of genre

The book has its heart in the right place with its close, careful reading of Verma’s works, but it seems confused in terms of its structure. The question that haunts Gill’s book is: how does one write the biography of an author? It is a question that remains unanswered and, also, undoes the central quest of this book.

The book is too brief, too sparse and too uninterested in Nirmal Verma’s life to constitute as a literary biography. It is both an attempt and a complaint against literary biography. The author discusses the form of the biography and expresses his fatigue with the “hysterically researched biographies that recreate whole eras and milieus”. These biographies obsess over tiny, minute details of personal lives for which Gill has “no voyeuristic curiosity.” He, on the other hand, intends to use reading as a form of biographical excavation where literature becomes a source to the life and mind of the author.

Yet, while articulating his project, Gill recognises its many pitfalls. In a moment of self-reflection, he states: “I am excited by this idea of reading as a form of biographical excavation. Yet I am doubtful if it actually serves any purpose… To interpret fiction by extrapolating it to what’s real is to miss the whole point.” And, the book misses this point by juxtaposing life and literature without illuminating either of them in their own terms.

If literary biography is not a genre that Gill appreciates, he could have written a series of literary essays on Verma’s work. Like a book of criticism, the chapters are divided according to the themes that permeate Verma’s work. However, the author never moves beyond the anecdotal nature of the work to develop full-fledged arguments about Verma’s literary works. Thus, the book offers a kaleidoscope of rich fragments, but it fails to bring together everything into a cohesive argument about Verma’s life or literature.

Akshaya Mukul published his massive biography of Agyeya this year and, now we are graced with Vineet Gill’s reflective account of Verma. Both these books offer a serious, critical discussion of major writers in Hindi landscape and one just hopes that these works will mark the beginning of a growing interest in Indian literature beyond the English language.

Archit Nanda is pursuing a PhD in Comparative Literature from Queen Mary University of London.