Although it is a bit unimaginable, images of various artworks captured from archaeological excavation sites can become an excellent work of art in itself. The images, included in the current photography project of the famous archaeology photographer, Mohamed. A, entitled Buried Monologues, invoke a number of questions: How does archaeological data, otherwise a mundane entity, become a source of aesthetics? Where does one place artistic imagination that seldom figure in our scheme of thinking about history, in unfolding the past of Kerala? While these are the major questions, there are many such questions, which stoke one’s curiosity.

An interesting triadic relationship between three things – experience, information, and aesthetics – is the best way to summarise the photographs in this project, which is a part of the art show, Sea: A Boiling Vessel, being held at Kashi Hallegua Art Gallery in Mattancherry, Kerala. Sea: A Boiling Vessel, being presented by Cochin-based art collective Aazhi Archives, is a multidisciplinary show bringing artists, academics, and performers to explore together the unnoticed pasts and the fluid futures of Kerala.

Mohamed himself wishes to describe the current project as “a purely academic intervention, but in a deep creative capacity”. It unravels the pasts of Kerala through a photo-documentation of ancient engravings, rock art, and other artworks at various excavation sites in Kerala which Muhammad was associated with for the last 15 years. He captured images from Anakkara, Kadampuzha, Kakkodi, Parambathukavu and Pattanam, and rock drawings from Edakkal, Tovari, Marayoor and Ettukudukka. As described in the supporting text displayed at the venue, “It is a journey into our past and what remains of it. It is also about the exciting experience of the process of ‘unearthing’ the past.”

Anakkara-Stone circle excavation. Photo: Mohamed. A.

A relatively recent merger of data and aesthetics has spawned a plethora of interesting works, which, in turn, opened new fields of inquiry in both the academic and art worlds. Buried Monologues endorses this new-fangled ‘data aesthetics’ to bridge concerns about aesthetics and archaeological data. The data and the work of art produced using the data do not stand at separate ends on the discourse, but, the discourse rather addresses an overt conflict between archaeological data’s objectivity and the subjectivity of artistic creativity.

Likewise, to the photographs used in this exhibition, excavations are both a process of unfolding the ancient or early medieval history of Kerala and sources of art production as well. It, therefore, becomes impossible for the artist to picture them without simultaneously capturing and deconstructing them.

Though Mohamed has been officially a part of several archaeological excavations in Kerala, the images he used for this project do not arise directly from his ‘experience’ but from a filter over experience, which he himself wishes to term ‘information’ (data). He focuses on the level of information, looking neither solely at history nor at the images made out of it, but at the filters between the two.

Ettukudukka, Kannur engravings. Photo: Mohamed. A.

Mohamed has devised a distinctive method, intending not to directly present the past of Kerala as unfolded through excavations, but doing it through a selective unfolding of experience using artistic resources. Thus, in this project what ‘official history’ considers merely an artist’s imagination or creative expression, stuff is provided for an alternative imagining or re-imagining of history to pick up. The project actually raises an interesting question, should these images be treated merely as providing illustrative supplements to a history constructed on the basis of tangible archaeological pieces of evidence, or can they be allowed to provide a component for reimagining history from an artistic perspective.

Challenging the anthropocentric imagination of history with an assumption that our past, present and future are connected by a certain continuity of human experience, Mohamed has given a sense of agency to each archaeological artefact he photographed. Natural patterns of laterite and granite stones, for instance, are pictured giving them the potential to narrate their own stories. As C.S. Venkiteswaran, art critic and the curatorial advisor of the show, says “these images – all too real but equally mysterious and enigmatic – take us on a journey that is material as well as abstract”.

Buried Monologues also addresses lacunae relating to visual knowledge of ancient and medieval rock arts of Kerala. The study of rock art as a visual register revealing the relationship between the symbolic production of it and the experiences and motivations (social and religious) of its creator has been a field of bourgeoning interest in the archaeology of religious practices, though it remains to be a relatively unchartered terrain in India.

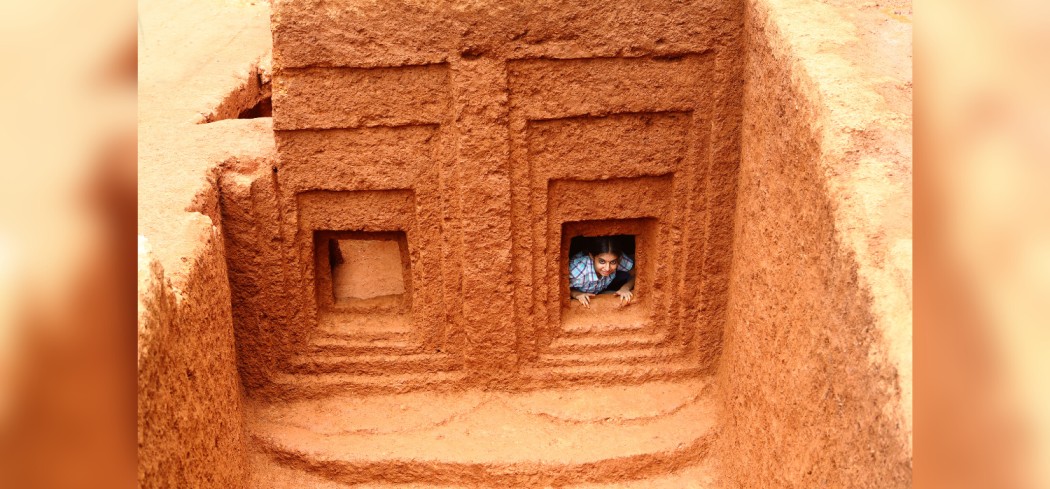

Pattanam excavation – Architectural structure. Photo: Mohamed. A.

Much has not been written or discussed about the system of social meanings that the circulation of such symbols created or no detailed analyses have been done on the practices and motivations behind their production, especially in the context of Kerala. Moving beyond the conventions of semiotics, Buried Monologues in making sense of motivations keeps a concern over the transience of humans and the immortality of objects, and the ways in which humans leave civilisation behind. This project also entails a profound move towards a form of production that breaks the realist conventions which come as a package with archaeological photography.

In Sea: A Boiling Vessel project, a separate segment named Origin Narratives has been included. This segment spans themes such as creation and origin stories of communities, episodic and fragmented memories of the past of communities, shared concerns over apocalypse, contested spaces of divinity, texts of travel, travel of texts, performative occasions, etc.

“In an act of narrating the past through the images of excavations and rock art, this project presents an alternative story of Kerala’s origin and evolution; how Kerala as a cultural and political entity came to be what it is now, how inward and outward voyages shaped it, and what the sea washed ashore in the form of objects and artefacts,” says Venkiteswaran.

A graduate of Fine Arts from the College of Fine Arts at Thiruvananthapuram, Mohamed never dreamt of Archaeology becoming his cup of tea. It was an assignment, covering the megaliths spotted in the fieldworks of the Department of History, University of Calicut, in 2005 that changed his destiny. Seeking the possibilities of creative interventions and moulding his own style in this partly academic endeavour ignited his passion for photographing the buried past.

“I gained further training through several travels across northern Kerala with Prof. Selvakumar, an eminent scholar of South Indian archaeology, who had a pivotal role in turning me into a trained archaeology photographer. The Pattanam Excavations, which started in 2007, was a milestone in my career. Destiny preserved some of the timeless remains of a bygone era under the soil, waiting for my lenses to be shown to future generations,” Mohamed narrates his journey so far.

The contributions he made to both Pattanam and Anakkara made him vital to Kerala’s archaeological community. “And Buried Monologues happened when I desired to bring archaeological photography onto the infiniteness of art ever present within me. This blend has been a tempting one throughout my career as an archaeology photographer,” Mohamed explains, how the idea of this project came in.

The show started on December 13, 2022, and continues till April 30. It is open on all days except Monday, and entry is free.

M.H. Ilias is a Professor and Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at Mahatma Gandhi University, Kottayam, Kerala.

Featured image: At rock cut cave Perambra excavation site. Photo: Mohamed A.

This article was first published on The Wire.