Many smartwatches and other digital fitness trackers have a function for measuring heart rate. However, a recent report from Stat News suggests that these heart-rate monitors may not be all that accurate for people of colour and the darker your skin, the less reliable the reading.

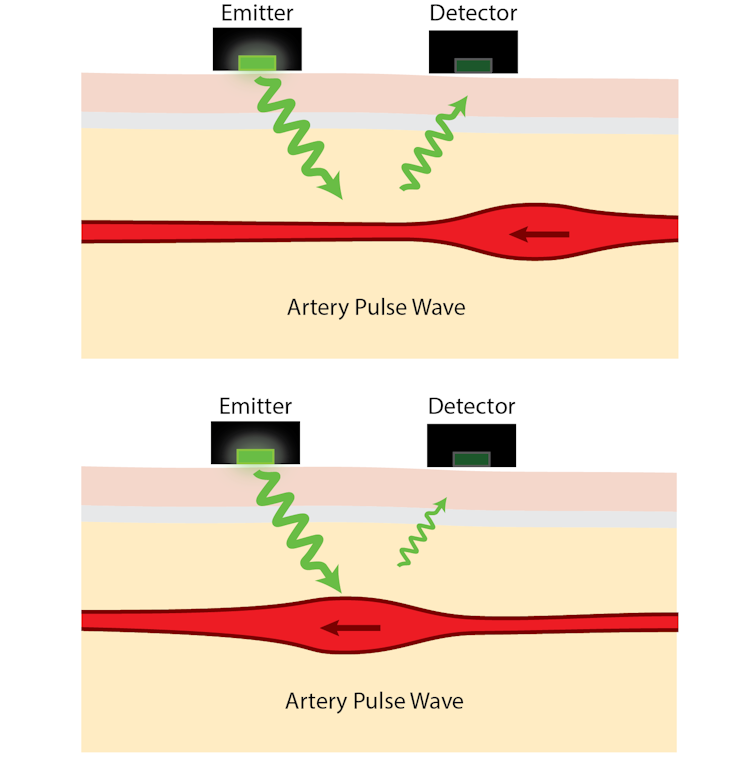

The most common wearable heart-rate sensors use an optical technique called photoplethysmography (PPG), which estimates artery volume using light. A wearable PPG sensor emits light onto the skin. Most of the light that penetrates the skin is absorbed by body tissues, but some is reflected. The amount of light that is reflected depends on several factors, one of which is the volume of arteries near the skin’s surface.

The blood in your arteries absorbs light better than the surrounding body tissues, so as arteries contract and swell in response to pulsating blood pressure, the intensity of the reflected light rises and falls. PPG devices detect this variation in reflected light and use it to estimate your heart rate. But achieving this reliably can be difficult.

T. Collins

Which light is best?

The choice of light colour in PPG sensors is a matter of compromise. Red and infrared light travels through the skin the easiest, allowing sensors to “see” more deeply into the body – picking up reflections not just from blood vessels but also from deeper tissues, including muscles and tendons. As a result, PPG sensors using red light can be more prone to interference from movement compared with other colours.

Red light sensors are also exposed to more interference from external light, which makes the heart-rate signal harder to isolate.

Blue light has very poor penetration into the body – so poor that it can only reach the tiniest blood vessels at the surface where the pulse wave is at its weakest.

Green light has better penetration than blue light, but worse than red. This means that green light PPG sensors can sense the larger blood vessels inside the body without too much interference from deeper tissues, giving a better contrast signal that is easy to detect and is less sensitive to motion errors than red light. So most consumer sensors designed to be used on the move, use green light.

Effect of skin tone

Skin colour is determined by the concentration of the skin pigment, melanin, with darker skin having more melanin than lighter skin. Melanin is a natural sunblock, it protects the skin by absorbing harmful ultraviolet radiation that would otherwise damage cells.

Melanin’s absorption of visible light varies significantly with colour. It almost completely blocks violet light but has virtually no effect on red light.

Green light lies in between these extremes. Its transmission through darker skin has been measured to be less than half of that through lighter skin. In PPG sensors, this difference means less light reaches the blood vessels of people with darker skin and so the received signal is weaker and more prone to error.

It is unclear whether people with darker skin would benefit from a different coloured light source. Red light, for example, passes equally well through all skin tones but, compared to green light, it gives poor performance (for all skin tones) in terms of errors caused by movement and by ambient light.

Does this mean that an activity tracker will measure heart rate more accurately for a person with light skin compared with a person with dark skin? Possibly, but there are other issues affecting PPG performance, including tattoos, how the sensor is worn (correct location and not too loose but not too tight), and how active the wearer is (optical heart-rate estimates are more reliable when you aren’t active).

Skin tone is certainly a factor that can affect the accuracy of wearable heart-rate monitors, but it is not the only one.![]()

Tim Collins is senior lecturer in Electronic Engineering at Manchester Metropolitan University and Sandra Woolley is senior lecturer in Software and Systems Engineering Research at Keele University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Featured image credit: Unsplash

![]()