“They said the workshop is inappropriate,” read the text sent by the head of the poetry club of a university in Jaipur.

I had proposed the ARQ-E-ZABAAN workshop to the university two months ago. Since then, we had been constantly communicating and planning to make sure students and other people from Jaipur could benefit from having an exclusive space to write and discuss Hindustani (a mix of Hindi and Urdu) language and poetry.

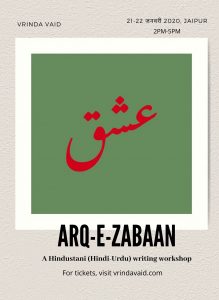

A poster of the event.

“They took down the posters and told us that they cannot permit this workshop to take place,” read another text.

I didn’t really have to dig deep into why the workshop was suddenly being deemed “inappropriate” four days before it was to take place. I have been running ARQ-E-ZABAAN for six months now, taking it to one city every month with the aim of getting people acquainted with a language that we get as a surrogate mother – only because we understand it to be Hindi – a language called Hindustani.

With social media opening wider avenues for us to be in complete proximity to almost everything that exists in the world, generation X has seen many drift towards the arts, tasting Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan sahab’s qawwalis as a child sitting with their parents and growing up to completely fall in love with a language that is a consummation of ‘sharaab’ and ‘shabaab’; a language of a destroying intoxication and defining beauty, very colloquially known as Urdu.

Over the past year, I spent time in self-educating myself about Urdu poetry, something that has long pulsed in my veins because of my father. While I was doing this, I also grew aware of how many people were listening to ghazals, say by Jagjit Singh, but had little understanding about its formation; or even the difference between a ghazal and a nazm.

Ruskin Bond’s words rung in my head constantly – his belief that the biggest risk that we run in present times is that we have more writers than readers. Our education seldom teaches us the extreme importance of reading, it is always confined to being a leisure activity and not something that must be cultivated, watered and consumed everyday, every moment.

As a result, when on the one hand people wanted to listen and never hear, there stood another lot that wanted to write but did not know how to. After all, a ghazal is a song or a poem – and not many dig deeper than that. With ARQ-E-ZABAAN, I want participants to begin understanding the essence of a language that is not just ours – but all of ours – and for people to know that Hindustani is an amalgam of Hindi and Urdu, a language that all of us speak, that we are in debt of.

Also read: Why Urdu Isn’t Just a ‘Muslim’ Language

When I began ARQ-E-ZABAAN, the world around me began to negate what I was doing without even knowing why I was doing it. I would hear constant skepticism in voices close and far as to why a 21-year-old was writing or teaching poetry and what career would she make out of this. But, the most painful among all the questions was why a Hindu girl, after completing her Bachelors in English, had taken upon herself to teach Hindustani – often understood as ‘only’ Urdu – because it was a ‘Muslim language’.

I would spend hours trying to make people understand the etymology and history of Urdu as a language, leave alone Hindustani; how it was birthed in Dilli, how the language is present in all of us because we’ve grown up with it, but most importantly, how language – any language – hasn’t gotten anything to do with religion.

Language makes art possible, it is a medium of unravelling the mysteries of the mind and the matter, it is how we understand the world around us. Zabaan likhne waale kee aur bolne waale kee muriid hoti hai, mazhab ki nahin. The world around me had started to understand, it had started to change.

I’ve had 45-year old doctors attending ARQ-E-ZABAAN because after spending a fair share of their lives serving others, they now want to spend the rest of their time serving themselves, immersing themselves in shayari and poetry because that is where they are at peace. They want to be free. Solace seldom has a language.

Jaipur was the last batch of ARQ-E-ZABAAN. The university administration did not want a ‘controversy’. They did not want a ‘controversy’ over a workshop on the study of a language. They did not want a ‘controversy’ on the study of a ‘Muslim language’.

There are two pillars to what happened. First, does language have a religion? Just to shake the ground a bit beneath your feet, the word ‘Hindu’ in itself is a Persian word.

Also read: From Dusty Books to Glowing Screens – How Urdu Got a Digital Revival

Second, the key word used to deem ARQ-E-ZABAAN not conducive of the stage was ‘inappropriate’. With a heart pregnant with sadness, I ask everybody reading; why now?

In present day India, there are new headlines each day on how India’s secularism is under attack. There was even a controversy over Faiz’s ‘Hum Dekhenge’ where “but” is very intelligently picked up out of a whole nazm to condemn it as a degradation of the Hindu faith. While some grapple with the idea of “context”, Faiz grins in his grave.

But, grinning at this juncture is not a privilege accorded to the living. Manjari Chaturvedi’s qawwali performance was stopped mid-way in Lucknow at an event organised by the Uttar Pradesh government. The noted Kathak dancer said she was told, “Qawwali nahi chalegi yahan”.

The wise would advise the 22-year old me to not give these events a “religious bias” but with how the narrative is unfolding daily right before our eyes, we’d be fools to think otherwise.

There stands a stark difference between a need and a want. Every person has an artist breathing inside of them. Every child needs a colour before they want a pencil. Art is essential to human existence. Language is essential to human expression. Can art, then, be divided on the basis of religion, much like how Hindustan was divided decades ago? It took years for the land, the waters, to soak in all that red. If art dies an innocent death at the hands of religion and politics, will the heart of a human be able enough to soak in their own blood?

Urdu is a dying language. If a dying language can make you feel so insecure, imagine what a living one will do to you.

‘Ek marti hui zabaan ki shanakht karna asaan nahi

log paagal ho jaate hain mare ko zinda dekh’

Vrinda Vaid is a writer and poet based in Delhi.