The author passed away in 2005, at the age of 95. This story has been submitted to LiveWire by her son.

In 1947, I was 34 years old and had twice been uprooted in my life. The first time was willingly from the Wiltshire village of Ramsbury when I married by barrister husband and came to live in Lahore in 1936.

The second time was when India was partitioned and, along with millions, I became a refugee.

I still regard pre-Partition India, especially Lahore, capital of an undivided Punjab, as one of the loveliest places I have ever known – lively, vibrant and friendly. Despite living in several cities across India over the past 50 years and thinking of myself as more Indian than English, I still cannot look upon August 15 as Independence Day.

To me, it remains the day of Partition, the tragic end of a cynical political game that divided the charming and varied India I came out to 61 years ago. Sadly, that cynicism has deepened on either side of the divide, leaving little room for optimism today.

But the months leading up to Partition are as real for me now as if they had happened just the other day.

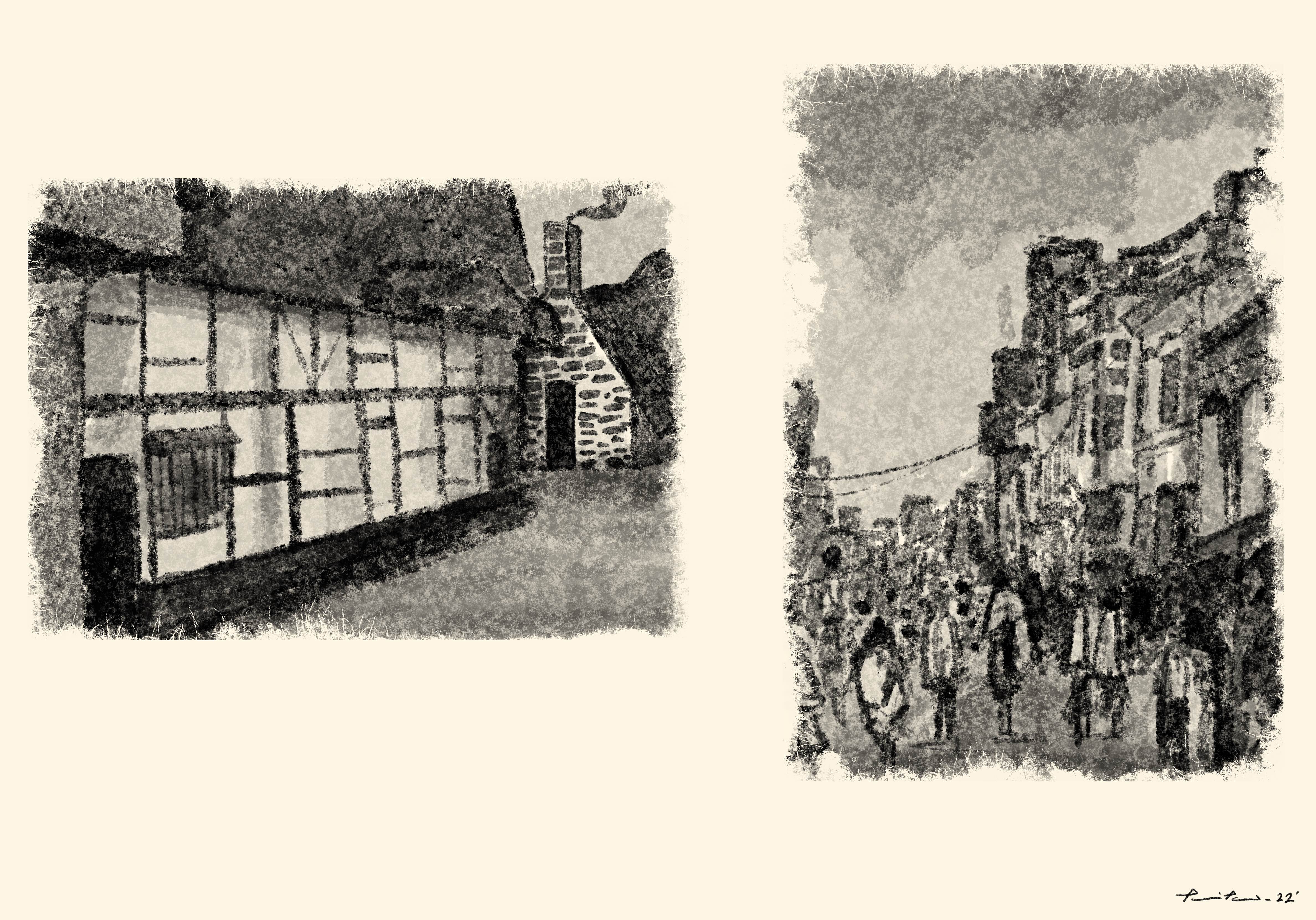

My most vivid flashback of those turbulent days is seeing an hysterical mob systematically looting and burning beautiful cottages belonging to Hindus and Muslims along Upper Bakrota, the fashionable area of Dalhousie, a picturesque hill town in northern India in July 1947.

Also read: The Pain of Partition, as Seen in the Literature of Many Languages

I realised that the exquisite cottage my husband Kuldip had been loaned for the summer by the barrister Anwar Mohammad, one of his closest friends from their days at Middle Temple, would not be spared, as the mob snaked its way up the hillside through the monsoon fog, armed with mashals (lighted torches) and hockey sticks.

Being the only Muslim house on this hill, it was a prime target.

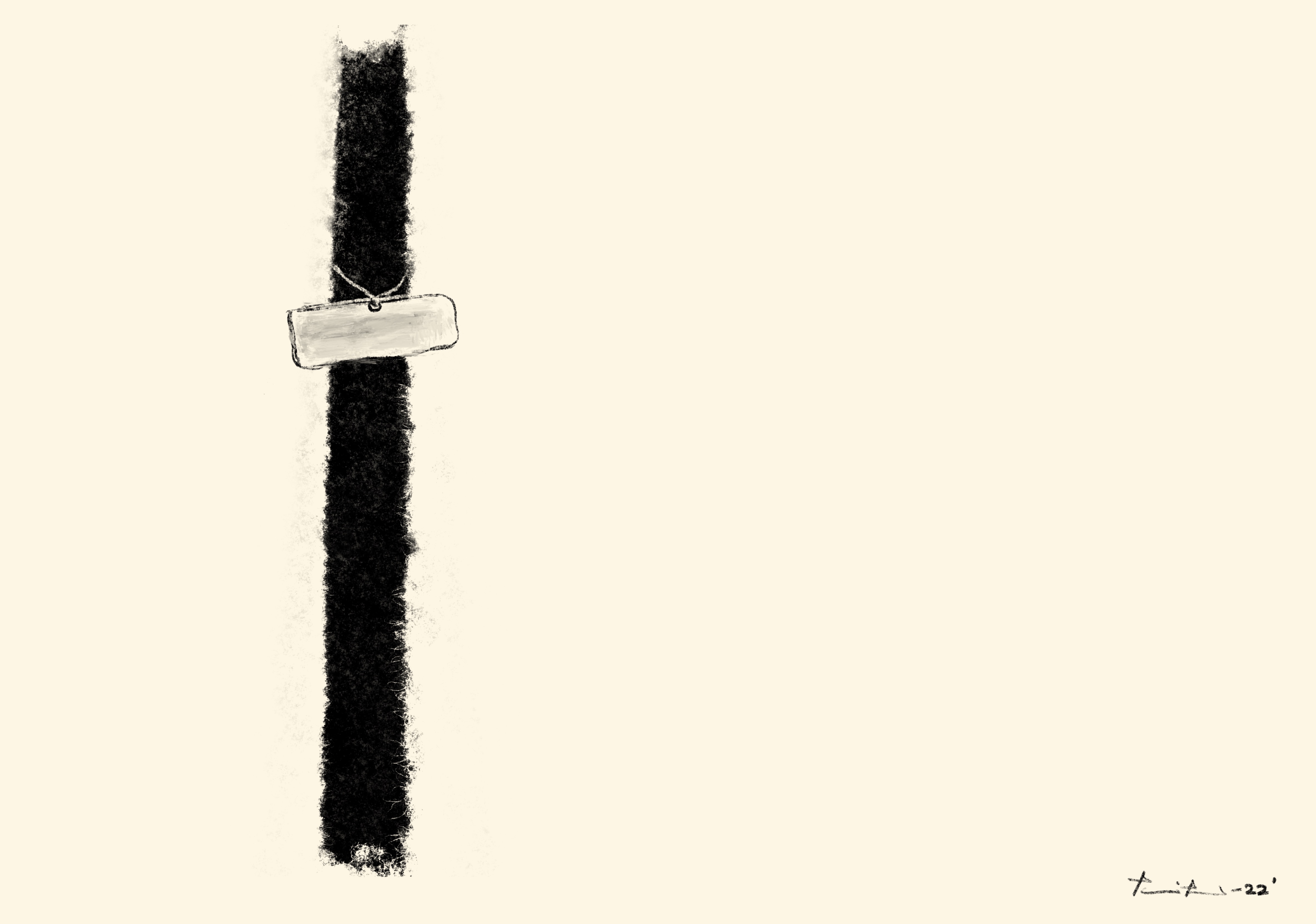

Quickly, my husband pulled off Anwar’s brass nameplate and, using my nail varnish, painted his own name on a piece of wood and tied it with wire to a huge pine tree at the entrance.

The vengeful Hindu mob turned down the flagstone path leading to our cottage, saw us standing in the porch and gruffly asked us to move so that they could burn down the Muslim’s house.

Also read: Memories, Pain, Remorse: A Partition Portrait Gallery

Pointing to the name plate, on which my nail varnish was still wet, my husband, not a Muslim, told the mob leaders that the house was his, bought the previous year from Mr Mohammad.

If they wanted to torch it, he told them, they would have to burn him too. He also told them Dalhousie was now Indian property and burning it would be a criminal waste.

The next few seconds were the longest I have ever lived through in my 84 years.

Maybe it was the collective fear on all our faces, or perhaps even our apparent determination, but for some reason the crowd turned around and headed up the hillside to ravage the neighbouring cottage which, ironically, belonged to a Hindu.

Though momentarily saved, our cottage was ransacked the day after we returned home to Lahore before fleeing almost immediately to live in partitioned India.

The temporary nameplate, bleached clean, and the tree to which it was tied were the only thing left of the cottage when we visited Dalhousie for the last time in 1951.

Back in Lahore, Hindu-Muslim riots had reached such a pitch as the August 15 deadline for independence neared and Anwar –who retired as a senior Pakistan civil servant – advised us to flee to Amritsar, the holy city of the Sikhs, 30 miles away, which was to be in India.

He promised to recover whatever he could from our house and somehow get it to us. We left with nothing.

I remember even leaving my watch behind on the mantlepiece, as we drove off in August, never to return.

All that was recovered some weeks later and sent to us was my husband’s prized Nash convertible, a Singer sewing machine, which still works, and a threadbare Persian carpet, discarded long ago.

We also never saw Anwar again, as over the years, fewer letters were exchanged till they stopped altogether as we settled into our respective countries.

It was a shame, as he was my husband’s closet friend and I still recall his wedding in Lahore a few months before Partition, when communal rioting raged across undivided India and sectarian distinctions were widening. Hindus and Sikhs were wary of Muslims and vice-versa. Apart from mob violence, there were innumerable instances of Hindus and Muslims poisoning each other’s water and food, often with fatal consequences.

Anwar was as aware of the poisonings as everyone else in Lahore. Since my husband was the only non-Muslim at the wedding feast, Anwar insisted, against his family’s wishes, that my husband eat out of his thali, guaranteeing his safety.

But such communal bonhomie evaporated with Partition, sadly obliterated by bitter memories of the chaos that pervaded the last few months. It was replaced by a visceral hatred which, unfortunately has transferred itself to succeeding generations, enveloping both India and Pakistan in endless, but needless, confrontation.

Illustrations by Pariplab Chakraborty. To view more such illustrations, click here.