“He knows that a lot of the literary people in college see books primarily as a way of appearing cultured,” wrote Sally Rooney in her book Normal People. “It was culture as class performance, literature fetishised for its ability to take educated people on false emotional journeys, so that they might afterwards feel superior to the uneducated people whose emotional journeys they liked to read about.”

I pondered upon Rooney’s brave and honest opinion about books being reduced to commodities while sitting at the Oxford Bookstore in Park Street, Kolkata. It was the winter of 2019, and I was on a date with the man I had been seeing for six years. He had flown in from Lucknow, I had flown from Bhubaneswar, and while geeting a cab together from the airport to our hotel, we had wondered if long distance relationships would have been navigable if we did not have the freedom to spend so much money.

Like books, love too is a luxury good restricted by social structures; such that marrying across faith comes off as a political conspiracy, marrying within your own sex feels like blasphemy and choosing not to marry becomes a West-influenced controversy.

So many people want to be normal at the cost of being happy.

At the bookstore, I saw him lingering around the corner of photo books, flipping through portraits and ghats clicked by Raghu Rai, before moving onto Koudelka, Bresson and Capa. Back in 2013, when we first started dating, we could only dream of owning these expensive photo books. We met at the Indian Coffee House on the noisy and vibrant College Street, where privacy for the common man came from his very invisibility, where the idea of an exquisite ambience was the comforting sight of so many lovers holding hands.

A cup of coffee cost Rs 17 there, so we spent hours talking, emptying one cup after another, till other customers started queuing up and we were literally shooed away. I did not know the coffee there was bland until recently, amazed at how all this while the sweetness had come only from the romance.

Also read: Growing up With Books: A Tale of Three Generations

Later, we spent the entire evening looking at books at the roadside book stalls near Presidency College, buying a Murakami or Carver for each other. He was what I talked about when I talked about love, I was his 100% perfect girl.

The death of libraries had already begun back then, so the second-hand book stacks at College Street were our sole support system. They were homeless, wanderlust books, carrying a wild charm which the domesticated volumes of libraries lacked.

Occasionally, you would find small notes on the margins of the pages written by the previous owner, their musings on the book covers and handmade bookmarks, making you feel a connection with complete strangers. It was an inexplicable feeling of intimacy.

On one of the copies of Anne Frank’s diary that I had bought, someone had jotted down, “little girls remind me of a valley full of flowers”. On some of the worn and torn Dostoevsky novels which had slept under the pillows of hundreds of heads, a small note would warn “unlike mine, I hope the next reader’s belief in God will not be shaken by the time this book gets over”.

In the first Milan Kundera novel I owned, strongly highlighted were the words “happiness is the longing for repetition”, which seemed like an intended message left for one of my bad days.

A first-hand book is a commodity, but a second hand book is an antiquity, carrying sentiments of so many hearts on which it had spent sleepless nights. It’s a legacy like your mother’s jewellery or father’s old watch – which has grown wise owing to all that it has seen.

I see no point of having personal libraries (why do they even call their bookshelves libraries if they do not believe in lending) and think books live and breathe only when they are exchanging hands, dog-earing the minds of people who dog-ear its pages, making a 70-year-old retired army man and a 20-year-old college student feel alike.

There are hugs hidden in hard-covers. On one unexpected evening, you will pick up a book and find the words etched on its first page, “To Eva, I hope you always keep this book with you as a symbol of our love”, and you will know that Eva did not keep it. She gave it away and it has come to you, and for some odd reason you will let out a sigh for two lovers you feel deeply for, but know nothing about.

The life lesson will hit you that love might be sweet but freedom is sweeter than everything else and sometimes, both do not mean the same. You will pass the book on without breaking the circle of life, to a lover you do not know you would later lose and you will write on it “till death do us part”. But death will never do you part, since your names will live on to be read and sighed upon, by children who are yet to be born.

By 2019, we could not afford to keep the fire in our hearts alive so instead we tried to rekindle it with lavish suite rooms which never saw love-making, expensive accessories and gadgets, since we hardly knew what authors the other person was reading at the time. Love became the rumour which everyone talks about but no one has seen: like demons, like justice, like god. Like the plot points of Imtiaz Ali’s films, which always need the assistance of Stockholm Syndrome to ignite compatibility; like a cover-up for relationships which cannot gather the courage for separation.

Also read: Mixed Feelings in Tow, Daryaganj’s Famous Book Market Finds a New Address

The separation happened. Cities changed, people changed but College Street remained the same. Crowded by inquisitive eyes scanning book covers to find one with protagonists which resemble them. Broken hearts and broken people looking for refuge in books they have already read since they know, they are prepared for the endings. I went looking for therapy like everyone else, in search of the right book.

“I had no one to help me, but the T.S. Eliot helped me,” wrote Jeanette Winterson in the book I randomly picked that day. “So when people say that poetry is a luxury, or an option, or for the educated middle classes, or that it shouldn’t be read at school because it is irrelevant, or any of the strange stupid things that are said about poetry and its place in our lives, I suspect that the people doing the saying have had things pretty easy. A tough life needs a tough language – and that is what poetry is.”

Last week, I opened the book again after almost a year. It wasn’t a breakup or the depression or the fights between mom and dad, but an event which none of the stories warned me about. A ravaging cyclone had swept through Kolkata, destroying the entire lane of bookshops. The pictures on the newspapers showed the distressed sellers, some of whom I know by name, standing in a pool of drenched and torn books, frantically searching for books which might be fine.

The media said it was a loss of at least Rs 60 lakh of business, but I am sure they do not know the real valuation of second hand books.

“That is what literature offers – a language powerful enough to say how it is,” Winterson had written. “It isn’t a hiding place. It is a finding place.”

I wrote a short note on the front page, just below the title Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? and kept it aside. Once the lockdown is over, I thought to myself, I would go to College Street and donate it to one of the bookshops so that the tradition can start again. But before that, I will wait for Kolkata to recover – the only city which looked beautiful even in its ruins.

Bijaya Biswal is a doctor and social activist working for LGBTQIA rights in Odisha.

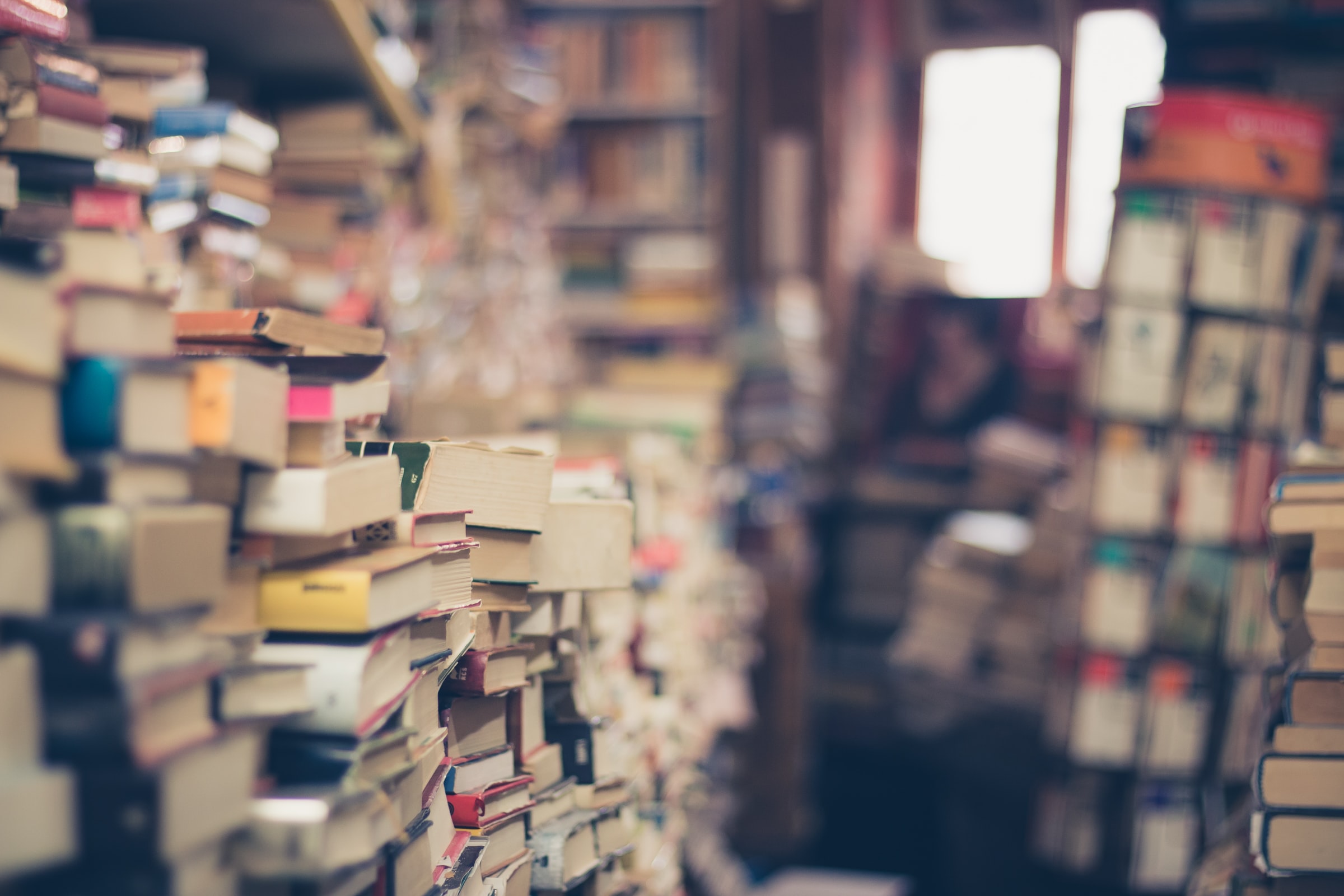

Featured image credit: Eli Francis/Unsplash