In an especially heated part of Kate Millett’s kaleidoscopic and anxiety-inducing memoir, Flying (1974), she sits down with the then veteran feminist and de facto leader of Women’s Liberation, Betty Friedan, to convince her that the liberation of gay people is central to feminism. The mood is fraught with tension, and on a lesser note, hope.

Unfortunately, Millett’s valiant defense falls on deaf ears. Friedan finds it preposterous that a youngster could lecture her about the goals of a movement she built from scratch. More so, she famously considered lesbians in the movement to be a “lavendar menace”, only good for blackening the movement’s image in the media. Even decades later, this episode remained a hotly debated encounter, and many consider it hard-proof that feminism has never had space for lesbians – or we would say now, queer women.

As the return of queerness to feminism is on the horizon, it’s worth returning to the question – did it ever leave? Unpacking this warrants a return to one of the most central figures in feminist history, Kate Millett herself. Flying is an ode to the ubiquity of lesbians in the American feminist movement of the 1970s. It’s a rushing, stream-of-consciousness style chronicle of the Second Wave Feminism in the US. A supercut of political meetings in university halls, interviews with uncouth journalists, periods of conflicts, unrequited love and misery – she explains that it “occurred to [her] to treat [her] life as a documentary”.

Flying

Kate Millett

Millett wrote Flying in the aftermath of shooting to fame after publishing her PhD thesis, Sexual Politics (1968), which was groundbreaking for its critique of how literature constructs gender roles in its portrayal sexual relations. This idea is common wisdom to even the average undergraduate literature student today, but it popularised a central idea to feminism: sex is political in character, not biological. Needless to say, Flying is an ugly cousin of Sexual Politics. It has been out of print for over two decades.

Sexual Politics is a text of the mainstream feminist movement, while Flying belongs to the lesbian feminists.

At least that’s what the conventional understanding of the second wave is. The current trend in feminist scholarship marks a disinterest in the history of the feminist movement, particularly Women’s Liberation, as philosopher Jean Curthoys argues in her book Feminist Amnesia. The lack of scholarly reflection on what the feminist movement has stood for is perhaps part of why “mainstream” feminism has become an unquestioned punching bag for many queer people today, but few ask whether mainstream feminism is purely a product heterosexual interests.

This is where Flying fills the gaps for us. If the Second Wave cliche, “Feminism is the theory, lesbianism is the practice,” is anything to go by, Flying shows us exactly what that means. Millett calls herself a lesbian in this book, though most refer to her as bisexual today, and boy, is she far from being the only one. The historical facts are, of course, very clear. Lesbians were among the first of the feminists who pitched in twenty-eight dollars together to register the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1968. In fact, they led the most radical programmes of many NOW chapters in many major cities. Being a lesbian was considered the practice of freedom from the confines of traditional womanhood.

Many today don’t consider the political lesbianism of the 1970s as “real” queerness, and reduce it to a political statement. Today the word indicates sexual orientation, along with words like ‘bisexual’ and ‘pansexual’ which have long entered the lexicon. But the Second Wavers had a more complicated relationship with the term. As Flying demonstrates, there was the blurring of lines between feminist and lesbian, friend and lover. Many times, for Millett, there’s a disorienting confusion of friend, lover and comrade. Her relationship with her assistant, Vita, is one of this kind, and it grows from latent jealousy to mutually destructive, laced with sexual encounters. Flying is not a celebration of being a lesbian, as Millett reconciles in the introduction,

“Under the banner of anti-monogamy there’s a a fine lot of sexual energy and experimentation in Flying, but people still get hurt… We want so much to be free, we still find it so difficult. We settle for less sometimes, especially these days.”

If Sexual Politics offers a grand theoretical framework of understanding relationships, Flying has smaller insights that are sheepishly admitted. One of them is that there isn’t hope for progress if people can’t learn to deal with jealousy. Millett was in fact married to Fumio Yoshiomura at the time, but most of her sexual relationships were with women. Several of them end in disaster and heartbreak, over which she spends much of the book agonising over.

Kate Millett is uniquely placed to offer insight into the place of lesbians in feminism. When Sexual Politics skyrocketed her from unknown sculptor to political celebrity, her private life became public spectacle. Her sexual practice became a measure for her politIcal commitment. On the one hand, she was proclaimed the unofficial face of the feminist movement to the general public and media, while on the other, she had to take the stand in front of the movement’s insiders and answer to their demands of what a ‘leader’ needed to be.

In a particularly painful episode following the newfound fame after Sexual Politics, Millett is forced to come out as a lesbian during a women’s movement meeting at Columbia University. This admission was later published in the TIME magazine, as a result of which her mother back home in St Paul was disgraced before friends, neighbours, colleagues and relatives.

For the people at the meeting, labelling herself a lesbian is cold proof of her being a ‘real feminist’. While it’s a gruelling experience for her and others, it also goes to show how central the idea of being a lesbian in the feminist movement of the 1970s. Despite how painful and unreasonable it sounds, Flying asks the reader to be sympathetic to the lesbian feminist experiment. Through its disorienting, vertigo-inducing prose, this book is a time capsule of an era of a popular movement.

Kate Millett and her fellow young lesbian radicals have an axe to grind; they have to stand their ground to the older vanguard of established feminist leaders as lesbians, whose lesbianism is part of their feminism. They are certainly not at the “margins” but at the epicentre of the movement, and placing them here makes most sense. If anyone was frustrated about the dissonance between feminist theory and practice, Flying is a thorough list of to-do’s and no-to-do’s.

Perhaps it still has some lessons to teach us.

Meghana Rupakala works as a teaching consultant at Azim Premji University, Bangalore. For her undergraduate honours thesis, she explored lesbian-feminist history in both France and the US, looking at how lesbians have contributed to feminism and the LGBTQIA+ movement today, and how this history has been lost or overlooked.

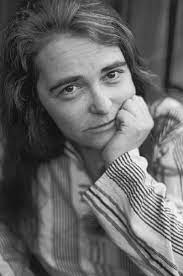

Featured image: Kate Millett